Killer Instinct – Evolution? Maybe not.

Written by Terry Houlding

For the majority, the term ‘killer instinct’ remains just that, a term. For others it is a known quality about themselves, which only they can truly recognize in others. In essence, the term has been described as a psychopathic quality that affects those involved in the killing of animals or another human being. In this context it is something that is said to affect 2% of the world's population. Although they are the only easily observable ‘test subjects’ a killer instinct in this regard is prevalent in soldiers as well as the obvious intrinsic link to criminals… One could argue “what makes a killer!”

More commonly it is associated as a hyperbole within the world of sports and to a lesser degree business. In sport, it is a commonly heard phrase to define the parameters of success in a player e.g. their killer instinct led them to being crowned champion!

The accepted definitions from various sources all point to it being a tendency or urge for ruthlessness or determination to dominate an opponent without the end result being their opponents death (in most civilized sports). Conversely, it is more associated in games that involve the element of chase as an integral component than say boxing or UFC!

It can be the crucial difference between two equally matched athletes as to who crosses the line in a race or stops the Polearmballl Runner in his tracks!

So where does it come from? The accepted norm and often the case is to go down the evolutionary path and claim that it is a throwback of our primitive ancestors who chased down and then killed their prey…. But wait! hang on, we’ve been told that we’re descended from primates. Last time I saw my chimpanzee cousins in the zoo; they weren’t swinging through the trees and hunting down antelope! If anything we were the ones being chased by toothier creatures! And like prey animals, children enjoy games of chase, for being the ‘chasee’ as much as giving chase, not exactly a sign of an evolved killer instinct.

Fast forward a few millennia to when our ancestors learnt to fashion tools for the purpose of killing. Back then hunting and chasing down prey was a survival trait and not necessarily a sport. However, having an innate drive and determination to succeed (in hunting) and therefore survive could be hypothesized to be a precursor to what we call a killer instinct.

This could then be said to apply to fighting amongst humans, be it to win in a battle, win a mate, or win the possessions from another. On an even larger scale when humans fight in battles for a variety of reasons, one of the overriding commonalities is the desire to survive.

Even this hypothesis has its flaws though… Many testimonies highlight that when in battle, the victor is often celebrated for the reckless disregard to his own life. Often, those who have thrown caution to the wind have risen to dominance.

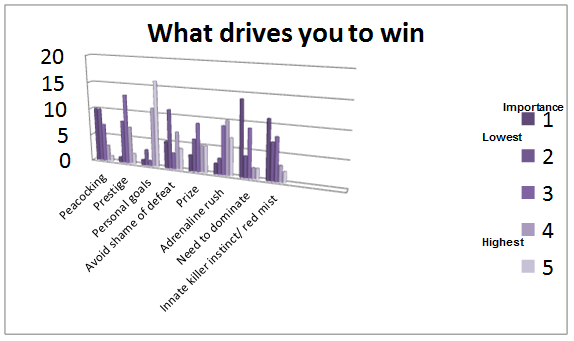

So if not one clearly defined factor, maybe there are contributing factors which we collectively call a killer instinct. In a target group of military officers who as part of their career, are generally athletic and participate in a number of sports at a competitive level, the question was posed; “What drives you to win?” with the caveat that it didn’t have to be the competition itself, just the element of chase as mentioned earlier.

In addition to the listed factors, they were also asked whether they recognized or attributed their drive for success to having an innate killer instinct. Surprisingly it was one of the lowest rated factors, with a similar lack of importance attributed to the need to dominate (introduced to see if people saw that differently to having a killer instinct).

What did top the results was personal achievement being the most important drive for success. This isn’t something specific to the target group but is commonly heard amongst athletes when asked to describe what lead to their success.

Despite all this, there is a clear difference between chasing a time or goal as opposed to chasing a human. When in a race; there is a clear psychological boost to seeing another racer ahead of you which spurs you to reach a speed/ pace unobtainable by yourself. Those who win however are without that spur at the final stretch. Maybe they have anthropomorphized the finish line, or even the time itself as a target, something to be beaten and not just a unit of measure or destination. In sports such as soccer, there is more to the game than just giving chase, tactics, positions etc. Racing over distance is much about willpower and stamina as it is about chasing an opponent or target. On the flipside, in sports where giving chase to ‘catch the prey’ such as the Runner in Polearmball who if goes unchallenged scores a Delivery (and in doing so disposes the opposing team of the representation of much needed resources) we see the other factors fly out the window to be left with the urge by the opposition to stop that player at all costs. Those with the killer instinct do, whilst those who don’t… don’t!

Interestingly when questioned in the survey “how competitive are you?” with the answers (“It’s the taking part that counts/ I tried/ I want to win/ I will win), only those who placed a high importance to Killer instinct also answered; “I will win”. So perhaps then, it is a state of mind, one that is self-taught or shaped and not the product of evolution. It would not be the first human trait that hasn’t come out of the primordial soup!

When I was first approached to write about this subject I thought I would find enough subject matter about the killer instinct in psychological articles etc. I thought that like most human traits and customs, it was clearly an evolutionary one as with many other things which we are led to believe through well respected academics”. However, not only did I find a lack of research or articles which substantiated this theory, even using it as a basis for success led to too many unanswered questions. This article morphed into what is in effect the precursor to a discussion which has no clear answer. Theories and hypotheses abound, but without factual evidence, only observations have been made with no real test groups to base them upon. What do you think?

Terry Houlding

is a freelance graphics designer, photographer and writer from Gloucester, UK. Having spent 10 years in the military, he sought to branch out from a rewarding career into a more creative direction. He lives with his wife, Natalie & daughter Ocean. They are preparing to emigrate to Australia to escape the terrible english weather and find a beach that is useful for more than just keeping the sea at bay. His website and work can be found here: www.nataliehoulding.com

The thrill of the hunt. The chase down and the kill...

Chase Down or Bust

by Sam Taylor

The thrill of the chase. Killer instinct. Two set phrases that are immediately recognizable to people of any generation in almost any part of the English-speaking world. Each can be used in any number of contexts – sometimes in a literal sense but more often as a metaphorical description of an everyday situation. Both phrases, whilst describing two different concepts, possess a certain something that makes them relevant to so many people in so many ways. It can be argued that, that something is a shared basis between the animal kingdom and mankind.

The human species evolved out of an ancient past and prospered whilst living much in the way that other primates do today. We can discern a great deal about the way that ancient man lived by looking at our modern selves – much in the same way we can speculate about the past lives of any species, living or extinct. For example, we know from the fossilized teeth of dinosaurs what they ate. The same principle applies to humans – we know that humans are omnivores and were as such throughout antiquity. Typically, meat eating species in the wild will rely on hunting to survive. Of course, there are exceptions – scavengers, for example, or animals that have learned to rely on other sources – but in carnivorous species we often see other adaptations that serve the primary purpose of aiding the animal in catching its prey – humans, again, are no exception.

The cheetah is the archetypal example of a carnivorous animal. Powerful legs propel it short distances towards fast-moving prey and long claws aid in bringing it down and allowing the big cat’s sharp teeth to do their work. Whilst the similarities may not be immediately obvious, scientists believe that humans too are perfectly adapted to run down prey.

Central to this theory are a number of adaptations. The make-up of a leg, for example enables modern humans to maintain speed over relatively long distances. Unique to humans, the Achilles tendon allows an efficient transfer of energy between the leg and the ground. In addition, the muscles providing this energy have a relatively high concentration of slow-twitch muscle fibres – those best adapted for endurance. To further aid our athletic performance over long periods of time, we humans have emerged from the animal kingdom relatively hairless. Far from an aesthetic consideration, this allows for superior heat transfer to the atmosphere. Our ability to sweat and cool rapidly means that an in-shape human can sustain a period of physical exertion for far longer than most animals can.

Persistence hunting was a technique favoured by many ancient humans and it is practiced to this day in parts of Africa and Central America. Human hunters give chase to their quarry, knowing that whilst they will be outrun at first, the animal must slow to pant and cool down. So long as the hunters can remain on the trail of the animal, success is merely a question of time.

Prior to the advent of farming, the survival of an individual human, or a community would depend on their ability to acquire food from nature via hunting methods such as that described above. Thankfully, the same evolutionary pressures that helped shape the modern human leg for hunting prey also influenced the survival instincts of the modern human brain. The world into which Homo sapiens emerged was very much a ‘kill or be killed’ situation – survival of the fittest. And in this case that meant the ability to kill and eat other animals.

Thus, our ‘killer instinct’ is a real part of our genetic make-up. The ability to, in the right circumstances, take the life of a living thing is hard-wired to a greater or lesser degree in our brains. Fortunately, in modern life, few people do all that much killing. The same psychology, however, may be apparent in other activities that are more far common.

Take, for example, the world of business. Top executives in banking and finance, or heads of companies completing hostile takeovers are often said to have ‘the killer instinct’. Here, it refers to an unrelenting aggression, decisiveness and confidence in the face of adversity. For those who are successful in such endeavours, the psychological mechanisms at work have amounted to a competitive advantage as they may have thousands of years ago – far before civilisation, let alone big business.

Perhaps the best examples of humanity embracing and ‘re-purposing’ its biological and psychological adaptations though come from sports. Indeed, the act of chasing an opponent has given rise to some of the most memorable of sporting moments. Consider the drama of a two-car duel in motor racing, the excitement of a late comeback in an athletic track event or the tension of a last minute breakaway in a soccer match. When the chase is on, particularly if ‘hunter’ and ‘prey’ are closely matched, adrenaline pumps and hearts beat faster – not only for the competitors but for team members and spectators too. Much of the pleasure we derive from sporting competition comes from our deepest-rooted instincts and one might argue that the purest form of this phenomenon comes from such chasing moments.

This concept has not previously gone unnoticed. The video game industry for one knows all too well that chase scenes or sections can easily create drama or action. The creation of the Runner position in Polearmball, however, surely represents one of the first explicit and deliberate exploitations of the chase instinct outside the virtual world.

The enjoyment that a player receives from playing Polearmball, either as or opposing a Runner, also taps into this age-old network of survival instincts and biological adaptations. The Runner carries the Polearmball with the aim of making it across the delivery line and back to their village. The avocado-shaped ball represents vital supplies for their team, thus successful retrieval of the Polearmball means life, and failure means death. Equally so, failure to capture these supplies represents failure for the opposing team and resources are scarce. Effectively this creates a kill or be killed situation.

Plainly, the opposition will require a razor-sharp killer instinct to successfully disrupt the supply of goods to the Runner’s village and save their own, but to make a kill they must first catch the runner. Perhaps much of what makes the game stand out from other sports is that it has been designed specifically to hijack human instinct, and to provide the high-adrenaline excitement of the chase as a central feature, not an incidental highlight.

For the first-time Polearmball player this leads naturally to two key pieces of advice:

Firstly, you must rely on every ounce of intuition and instinct as well as your athletic prowess if you wish to be victorious.

Secondly – and perhaps more importantly – enjoy the game – it is, after all, in your nature.

Sam Taylor

Sam Taylor is the Author Of This Article

Sam is a freelance copywriter, living in the south of England. After completing a bachelor’s degree in linguistics he worked as a web marketing consultant before choosing to specialize in copywriting. Before choosing to go it alone as a freelancer, Sam learned his trade with a top British marketing agency, creating compelling content for global brands and local start-ups alike.

Sam now writes primarily for small organizations on the projects that interest him most. He devotes most of the time to writing and playing music with his bands.

Prey Drive: the Chase and the Catch

By Mark A. Latham

For millennia, mankind has been driven by the thrill of the chase. The hunt, the pursuit of a partner, the games we play as children, the exhilaration of watching a high-speed pursuit, or the adrenaline rush that comes from fleeing our pursuers. Humans and animals both share a primal joy of the chase – a phenomenon known as the ‘prey drive’ – and it’s a part of everyday life. Whilst in nature a prey drive is vital for survival, in human society it can be seen in everyday life – our jobs, our love lives, and our games. It’s no surprise then that the chase (and, partly, the kill) is a fundamental part of a new and innovative sport: Polearmball.

What is Prey Drive?

First, let’s discuss the fundamental misconception about our love of the chase. Prey drive (also called ‘predator drive’) is not the same as aggression. It is a natural, enjoyable response to chasing down a target, and is present in all predatory creatures. Dogs and cats often chase ‘prey animals’, but they don’t always kill what they catch – the experience of the chase is enough for them. You could equate this to the fisherman who spends all day waiting for the big bite, only to put his prize catch back in the water before he leaves. I’ll talk about killer instinct later – prey drive and killer instinct are two very different things. That’s not to say that getting chased by a predator is safe! There’s some truth to the old saying that you shouldn’t turn and run if you encounter a bear in the wild, for example – movement triggers the prey drive, and a predatory creature will instinctively pursue something that runs from it – and unlike most humans, bears do have a killer instinct!

Whether you’re a man, a bear or a domestic cat, exercising a prey drive unlocks a sequence of actions: The Search, the Stalk (or ‘Eye Stalk’), the Chase, the Grab, and, finally the Kill. Some animals concentrate their energy on different areas of this sequence. For example, a bird of prey will spend most of its time hovering above a field, waiting for prey to make a move (the Search), whereas a wolf pack will ‘cut to the chase’ very quickly. A farmer herding his flock relies on the stalking ability of his dogs – their ability to stare down sheep and almost entrance them is the key to directing herd animals.

The Hunt

Of course, hunting isn’t just the remit of predatory animals. Humans have been hunting prey animals throughout their history, and in many parts of the world it is still a primary source of food. However, in western culture particularly, hunting has been refined into various disciplines, partaken as a hobby rather than a survival tactic. As recently as a decade ago, fox-hunting was enjoyed as a sport in the United Kingdom. The red-coated hunters on their horses would pursue a fox, using a pack of hounds to follow the fox’s scent trail. What is unusual about this pastime is that it is not hunting for food, but rather for extermination – the fox, if caught, is killed by the hounds. Dogs used for fox-hunting are not the typical canine companions we’re all used to having in our homes – they’re allowed to retain some of their pack mentality, and are encouraged to have a killer instinct. Unlike your average pet, these dogs use every part of their prey drive. The reward for the human hunters is the thrill of he chase, the joy of success, and a traditional toast to ‘the day’s fox’. These days, fox-hunting is banned in Britain, but that doesn’t stop the hunt from taking place. The dogs, bred for so long to hunt and kill, would make for pretty poor pets; and so now human runners are employed to lay a scent trail across-country, which the hounds then chase. They don’t get the kill any more, but they do still experience the chase, which is enough for most dogs.

Sticking to the British Isles for a moment, it’s worth mentioning the old hunting practice of deer stalking. This is particularly popular in Scotland, where the great expanses of rugged land and forests nurture large numbers of wild deer. In deer stalking, the emphasis is on the search – the stalkers will spend hours looking for a prime vantage point, and then spend several more hours waiting silently and patiently for a deer to cross their sights. They stay downwind at all times – moving position if the wind changes – and then only take their shot if they can ensure a clean kill. Imagine spending hours in the cold, wet Highlands, finally finding your deer, and then not pulling the trigger! Yet deer stalking is an ancient and honourable pastime, and the hunters believe that no animal should suffer unnecessarily.

These tactics and formalisations of old hunting methods are nothing new to man. When we think about great hunters, we often think of the Native American Indians, who lived according to the ever-changing hunting grounds of the Great Plains. They hunted buffalo before the introduction of the horse to North America, and afterwards became some of the finest horse archers in history, chasing down the herds of buffalo on horseback. The Native Americans also bound hunting in ritual and honour, not only to ensure success on the hunt, but to appease their gods and ensure future success, too. Hunters would be blessed before setting out, and the great spirits would have to be appeased to guarantee favourable conditions for the hunt. The hunters would be adorned with charms and sacred face-paint, and would compete with each other for the cleanest kill, the most kills, the taking of the largest animal, and so on. Once they returned to camp, the animals would be butchered. Every part of the creature would be used – the bones for tools and jewellery, the skins for clothing, headdresses and hides, and the meat for food. Sometimes parts of the animal would be offered to the spirits, so that they would reward the tribe with good hunting grounds the following season.

We might think these rituals and traditions strange, but think about it – how many people who go hunting carry a lucky rabbit’s foot, or wear their lucky socks? Even in sports, which I’ll come to in a moment, how many players do you see touching the turf when they run onto the football pitch, or kissing the lucky tattoo on their wrist when they score in a soccer game? Ritual, psychology, tradition – these are things that separate the human hunter from the animal.

Let the Games Commence!

Human beings have an almost primal need to release those pent-up prey drive instincts. Modern life has removed much of the danger that our ancient ancestors had to endure, and in an increasingly urban society not everyone is able to (or wants to) go hunting at the weekend. But humans are the most adaptable creatures on the planet, and so we’ve invented a whole host of ways to exercise our prey drive. We call it: sport.

Most competitive sports involve an element of chase that is integral to victory or defeat. In soccer, you chase the ball, but you have to outpace and outmuscle your opponents to do it, releasing those same emotions that the Native Americans did when vying for the biggest buffalo on the plains. In American football (and rugby), the physical side is ramped up a notch, and you stalk and chase the quarterback before he can score (whereas the quarterback chases the ball). Tackles can be considered the ‘grab’ part of the pursuit – just like a cheetah tripping an antelope in the wild. In either case, there’s always a target, and a reward for catching the target. In Polearmball, as in football, a designated Runner is sent off with the ball to score, and the opposing team must chase him/her down. If they catch the Runner, they can contain him, or metaphorically go for the ‘kill’ – but of course, first they have to get past the Runner’s teammates!

In competitive athletics, or even motorsports, you could be forgiven for thinking that the chase instinct isn’t exercised. After all, you’re not chasing each other down, right? Well, not entirely – the frontrunner is actually chasing the finish line, and the reward that comes from crossing it. The other competitors are really chasing the frontrunner, because that person is preventing them from claiming the reward for themselves. Obviously there’s no tackling involved (that would be bad!), but the emotions stirred are exactly the same as when hunting and chasing prey. Having someone ahead of you in a race is the thing that spurs you on, giving you the adrenaline rush to go that extra yard.

Remember earlier I mentioned watching chases can be just as exciting? Well, it’s true – it’s not quite as exhilarating as being involved, but if you have a stake on a horse or a greyhound at the races, or if you’re heavily invested in your team’s performance at a football game, you’ll release all of that adrenaline and all of those emotions, just as sure as if you were out there doing it yourself.

Doing it for Real

Watching spectator sports isn’t the only way to release that adrenaline in a ‘voyeuristic’ manner. Ever watched a high-speed pursuit on World’s Wildest Police Videos? The only way to make a spectator event truly exciting, without having your team’s victory riding on it, is to add an element of genuine danger. We thrill to police pursuit footage because we don’t know how it’s going to turn out. Maybe the criminal will get away; maybe they’ll be arrested; maybe someone will get hurt, or even killed! It’s that uncertainty of the outcome that makes us experience the chase vicariously through the people on our TV screens.

But what about the people that do it for real? Well, the cops who’re out there chasing down dangerous criminals, or the soldiers in far-off lands hunting insurgents every day, don’t have to imagine what it’s like to have a well-honed prey drive. They’re uniquely placed, because they live it every day. But there must be other ways for humans to exercise a prey drive? The heroes of the emergency services and armed forces can’t have it all, can they?

Human society has come a long way. Our social interactions and customs have watered down many of the primal instincts that we used to use on a daily basis. We do perform ‘the chase’ more often than you might think, just in a modern form. Think about the emotions and physical responses you might have been through when you’ve been ‘chasing’ a job at interview, or maybe ‘chasing’ a deal at the office, or maybe you and your partner have been ‘chasing’ your dream home. If you failed, remember how frustrated you were? If you succeeded, remember how elated you were? That’s those same instincts coming to the fore again, just in a different form.

And remember the old saying ‘the chase is better than the catch?’ You’ll never find a better example of the prey drive in men than when they’re trying to get involved romantically with a woman. And the reason the chase is better than the catch is because it’s thrilling. There are twists and turns. Gone are the days of early man when we’d just hit our beloved over the head with a club and drag her back to our cave. Now we have to work at it, like the patient hunter.

The Killer Instinct

Through all of this, I’ve maintained that the killer instinct is separate from the prey drive. You don’t have to kill what you catch. As in Polearmball, the kill is a strategic choice, not an imperative. When predators play, they simply chase and that’s enough – like kids playing tag in the schoolyard. But when the stakes are high, all predators have to be able to finish the job, and deliver the killing blow. Psychologists believe that only 2% of modern humans actually have the capacity to kill another human – that doesn’t take into account soldiers, as they are believed to enter an altered state when they’re in a war zone. But we do have the capacity to score a goal in soccer; to pull the trigger when stalking a deer; to dig deep and beat the other guy in a marathon; and to give the girl our number. In modern life, the killer instinct is not as primeval as out in the wild. We have become something very different to our forebears – we have developed reason, and wisdom, and a sense of responsibility. It’s in harnessing these things, along with our more primal urges, that allows us to emerge truly victorious from the chase.

Mark Latham is an author, editor and games designer from Staffordshire, UK. Formerly the editor of Games Workshop’s White Dwarf magazine and head of Warhammer 40,000 in the games development team, Mark is a writer of short stories, books and tabletop games, such as Legends of the Old West, and Waterloo. Mark has been ensconced in the worlds of science fiction and fantasy for many years, but his real passion is for history. Mark has a deep obsession with the past, especially the nineteenth century; an affliction that can only be salved by writing on the subject for far longer than can be considered healthy.

Mark's web sites are here: thelostvictorian.blogspot.co.uk

and here: www.facebook.com/thelostvictorian

Mark Latham

| ||||||