"Face-painting in Polearmball is integral to individual and team identity. "

"It is also a practical way to score points."

Face-painting Through the Ages

by Mark Latham

In Polearmball, face-painting is an integral part of individual and team identity, as well as a practical way to score points. But when the average person today thinks of face-painting, they’re more likely to think of those cute animal designs that get put onto kids’ faces at parties, circus clowns, or the painted flags worn by soccer fans at the World Cup. This article seeks to redress the balance, by looking at the history of face-painting, from its beginnings in ancient warrior societies through to modern usage.

The history of face-painting dates back thousands of years, and has been used for all manner of purposes: camouflage for hunting, war paint for intimidating the enemy, magical designs for use in religious ceremonies, and, of course, beautification.

Ancient Hunting Practices

Early man devised body-painting pigments, such as ochre, long before they started drawing on cave walls. What we know from ancient Mesoamerican tribes is that early body painting was not just used to denote tribal identity, but was also used to break up the silhouette of the tribesmen’s bodies, thus camouflaging them in the dappled light of their forest homes. Even today, hunters armed with rifles smear their faces with dark paint or even boot polish to disguise themselves when stalking prey – human or animal, and present-day soldiers use the same techniques when on covert maneuvers in the dark. It’s an ancient but effective method of blending in with one’s surroundings.

War Paint

Wearing face-paint to war has not always been about camouflage, but also about identifying warrior bands and frightening the enemy. For example, movies like Braveheart depict the blue ‘woad’ paint as a Celtic staple. Although it wasn’t used as recently as that movie suggests, blue face-paint was certainly used by Scottish and Irish warriors for many centuries. It was the fearsome appearance of Scottish clansmen that led to the Romans constructing Hadrian’s Wall in 122 AD, to separate Roman-occupied Britain from the wild highlands of the north.

The most famous proponents of war paint, however, were the Native Americans, who applied face-paint for this purpose for thousands of years – right up to the plains wars of the late 19th century. Their war paint was made from diverse ingredients – white clay, flowers, berries, plant sap, tree bark and even manure! And it wasn’t just used to intimidate the foe, but also to denote status within the tribe, and to grant the wearer special powers. The designs of Native American face-paint varied from tribe to tribe; for example, the Akicita used a lightning bolt pattern, which they believed made their warriors faster. Colors, too, were carefully chosen by individual warriors, or ‘braves’ – black was often thought to signify power, red would provide vigor, whilst yellow was a sign that the warrior was willing to fight to the death. After the battle, the braves would often repaint their faces for the victory celebrations, with black paint symbolizing a crushing victory!

Ceremonial Face-paint

Shamanistic rituals the world over have involved the use of face and body painting for millennia. The Native Americans held rituals and dances to bring victory on the hunt or in battle, to bring the rain, or simply to call the blessing of the gods. In Britain and parts of Europe, the Druids also painted themselves with various symbols as part of their ancient rites – symbols such as the triskele were thought to bring the blessing of the triple-aspect goddess, while the circle or ‘wheel’ represented the cycle of life and the seasons. Similar examples of shamanistic face-painting can be found from African tribal cultures and the Aboriginal tribesmen of Australasia – religious face-painting was incredibly widespread. Even today, in religions such as Hinduism, face-painting is widely employed. Nowadays practicing Hindus tend to use dots or lines. The red dot, or ‘bindu,’ applied between the eyebrows, is a blessing derived from the red powder that was traditionally offered to God. The lines, depending on their orientation, signify a follower of either Vishnu or Shiva.

Face-painting in religious ceremonies was perhaps a way for the shaman, priest or medicine man to take on an otherworldly aspect – to distance himself from his worldly form and attune himself more closely with the gods or spirits he was trying to appease.

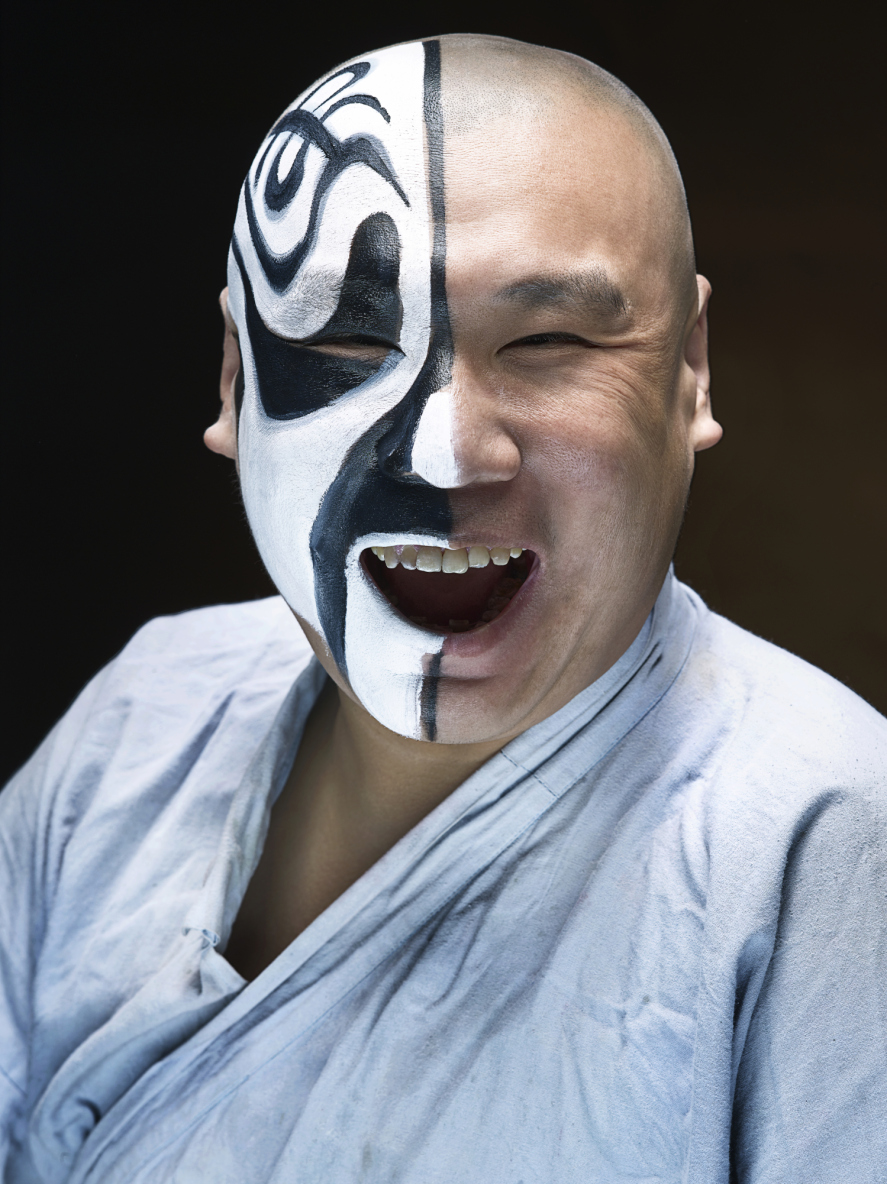

Entertainment

The ancient religious ceremonies touched on above often involved dancing and storytelling, and this is probably what led to the use of face-painting in entertainment. The Kabuki of Japan, for example, is a traditional form of entertainment featuring ‘singing, dancing and skill.’ The dancers are famous for their elaborate face-paint. This type of entertainment in turn gave rise to the traditional circus clowns that we all know today. But even clown make-up has a long history. There are many types of clowns depending on which part of the world you’re in, and professional clowns take great pride in designing their own unique make-up, because it’s integral to their identity. In fact, since 1947, clowns have been able to register their designs with ‘Clowns International’ in the UK, by providing a copy of their face-paint painted onto an egg!

Fashion

Of course, face-paint of a sort has also been used for beautification for centuries. The ancient Egyptians famously used elaborate kohl eye make-up, which was the ancient precursor of today’s eyeliner. In Japan, the Geisha wear thick white face-paint with stylized eye and lip makeup. This style began to evolve as early as 794 AD, and was formalized in the way we know it today in the 18th century. On the other side of the world in the 1500s, the English Queen Elizabeth I popularized a similar form of white face-paint, which she used to hide her wrinkles as she grew older. By the late Elizabethan era, both men and women were using face-paint, beauty spots and rouge to alter their appearance. This bizarre practice would ultimately evolve into the cosmetics used today.

Sports and Polearmball

Face-painting has become common across the world, for a host of reasons. However, the way we see it used most often today is at sporting events, where supporters of teams use it in an almost tribal way to mark their team or national colors. Polearmball will take this one step further – like the warriors of old, the players will be encouraged to design their own face-paint, contributing to their score by successfully complementing their team identity, and even intimidating the opposition. When the call to arms goes up, every player will transform themselves, striving to be the most fearsome, unique and awe-inspiring member of their team – will you rise to the challenge?

Mark Latham is an author, editor and games designer from Staffordshire, UK. Formerly the editor of Games Workshop’s White Dwarf magazine and head of Warhammer 40,000 in the games development team, Mark is a writer of short stories, books and tabletop games, such as Legends of the Old West, and Waterloo. Mark has been ensconced in the worlds of science fiction and fantasy for many years, but his real passion is for history. Mark has a deep obsession with the past, especially the nineteenth century; an affliction that can only be salved by writing on the subject for far longer than can be considered healthy.

Mark's web sites are here: thelostvictorian.blogspot.co.uk

and here: www.facebook.com/thelostvictorian

All can be seen on the faces of young children at the fairground or at parties and that’s the image that springs to mind when we generally think of face painting. Travel the world and go back in time however and there was, and is; much more to face painting than the decoration of children.

In western culture, face painting’s roots stem from the arts and entertainment industry. Evidence of this can still be seen today in the Circus on the faces of clowns where, as well as to entertain, it was used to over exaggerate the emotions of laughter or sadness and thus reach the audience furthest from the stage. (This In western culture, face painting’s roots stem from the arts and entertainment industry. Evidence of this can still be seen today in th was also used in early Chinese plays where face painting replaced the use of masks to give better periphery vision to the performers).

Face painting in the arts harks back to renaissance times and was used by authors such as William Shakespeare where, instead of being used for aesthetic reasons (not withstanding that female parts were played by male actors), it was used to portray moral attitudes. Colours denoted various aspects of what was considered a corrupt society with red expressing sin, white seduction and poison black.

Following the renaissance, face painting fell out of favor in western society, only making a revival in the 1960’s as part of the anti-war movement with flowers, rainbows as well as other peace promoting symbology.

In Japan, Geisha girls were entertainers skilled in dancing, singing or the playing of musical instruments. Whilst some Geisha were known to entertain sexually, this was more as an accompaniment to their artistic skills. The Geisha girls spent hours painting their faces in heavy layers of makeup in a tradition that dates back to the 18th century. The level of makeup on their faces denoted their maturity with the younger pre-adolescent girls in training, being the most heavily painted whilst those who had reached maturity wore less to allow their natural beauty to show through or to denote their particular skill in their chosen art form. There are a few theories as to why they painted their faces. It may have been related to subjects of the Japanese emperors only being allowed to see him through a veil and the white face painting was employed to circumvent that (the white makeup acting as the veil). Alternatively it could have been used to mask the younger girls’ blushes when in the presence of men. The heavy white base layer was originally made from lead based paints until the poisonous substance was linked to the older Geishas terrible skin and back problems. Since then it was made from rice powder.

Face Painting goes well beyond the arts and finds its deepest roots in hunting. Early hunters found in existing tribal communities today (such as those in the Amazon) would use it to camouflage themselves. As it was being used as camouflage for hunting, it will have quickly spread into other aspects of human culture such as war, tribalism and religion.

In war, it would likely have been adopted initially as camouflage allowing raiding parties to sneak upon their enemies unseen (a practise still used in today’s military). Over time, face painting became more stylised and certain patterns gained more symbolism with some cultures believing that certain attributes would be bestowed on the wearer. For instance, Native Americans would believe a symbol of lighting would grant the wearer speed and power.

Face painting was an integral part of Native American culture. As well as conferring abilities to the warriors, it also told stories about that warrior. For example, a hand print symbol on the face would show that a warrior had engaged in hand to hand combat which in turn would not only enhance his own reputation but, when seen by his enemies, strike fear into their hearts! Colours also held meaning. For some tribes, black would denote strength and bravery or symbolise victory in combat. Yellow would be used to show that a warrior was either heroic or willing to fight to the death.

Face painting wasn’t just used for war though; it could be used by tribe members to show harmony with the colour green or the white of mourning. Animal designs/ aspects would also be used to show a warriors spirit guide (though they did not look like children’s face paintings today!) Paints would be made from plants and berries and combinations thereof. They would also use minerals such as Mica and coloured clays which could be found in riverbeds and streams.

Sometimes at its simplest, face and body painting was for protection from the elements and insects. The Redskin Indians gained their name from the red ochre that they painted themselves with for that very purpose.To early western settlers, the painted warriors must have certainly seemed terrifying and savage to them as they wouldn’t have this knowledge!

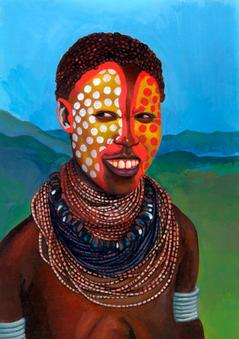

Face painting is also prevalent amongst African tribes. In most cases it serves a similar purpose to that of the Native Americans. One of the more extreme examples is that of the Haiti practitioners of Vodou or Voodoo as it’s more commonly known. Priests would paint skull-like images on their faces which held deep spiritual meaning representing rebirth and new life. The rock band Kiss are thought to have adopted their iconic image from Haitian Vodooism!

In Myanmar (Burma), many women are still seen wearing Thanaka, a powdery yellow substance used both as a cleansing agent for the skin and as a cosmetic to enhance their beauty. Rich women would sprinkle gold dust in the powder to flaunt their wealth and standing in society, while those less well-off would use ground up flower petals.

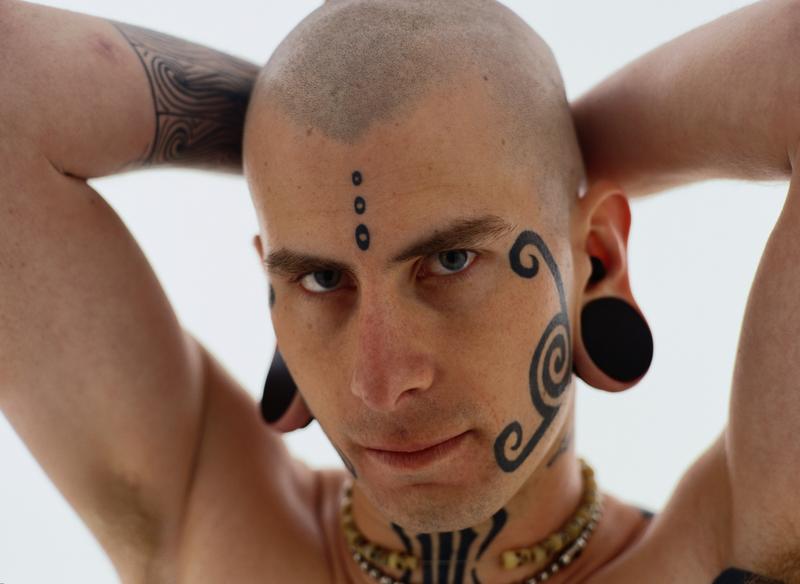

In New Zealand, members of the Maori tribes have designs painted on their faces. These denote a member’s tribe and caste (social status) and are, like fingerprints, unique to the individual as the painters will design the shape around the person’s facial bone structure and features. In Rugby, the New Zealand All Blacks use face painting to enhance their imposing aura on the pitch.

Face paintings earliest adoption in sport was thought to have been by the baseball legend Babe Ruth. He used black charcoal to paint stripes under his eyes which was said to reduce the glare of the sun reflecting off the skin.

Wrestling has used it to establish identity and used by legends such as Sting (the wrestler not the singer) with his iconic white face and black stripes and Jeff Hardy who sported a variety of designs. As his name suggests, the Kiss Demon modelled his likeness from Kiss.

Polearmball adapts many of the aspects of face painting as part of its play, both with camouflage, identity and to intimidate the opposing team as well as contribute to the final score.

Although it is unlikely that the small child you saw at the fairground has slain a tiger, there is more to the story of face painting than meets the eye.

Terry Houlding

is a freelance graphics designer, photographer and writer from Gloucester, UK. Having spent 10 years in the military, he sought to branch out from a rewarding career into a more creative direction. He lives with his wife, Natalie & daughter Ocean. They are preparing to emigrate to Australia to escape the terrible english weather and find a beach that is useful for more than just keeping the sea at bay. His website and work can be found here: www.nataliehoulding.com

"Tigers, rabbits, butterflies and pirates?"

The Lore and History of Face Painting

Written by Jeannie

Face paint in History

People have been painting their faces since time immemorial. It’s not new, it’s not innovative and the reasons why we humans do it has not changed at all, in all that time. The majority of ancient civilizations that we have evidence for, particularly those who had tribal systems, wore make up. This is true of the Celts in Europe, of Asian tribes in India, China and Japan, and in the southern hemisphere in Australia and New Zealand and among the ancient peoples of North and South America.

The use of body and face paint once provided a really useful way to identify friend and foe. Patterns of marking told the observer what tribe someone was from and what status they held within the tribe. The paint was also used in preparation for war and in spiritual and religious ceremonies. Many indigenous tribes in the southern hemisphere have held onto these traditions, whereas in the northern hemisphere, gradually we have seen a decline in the use of face paint, except for ceremonial or entertainment purposes.

In Ancient Egypt facial make-up was used to enhance beauty primarily, and yet it was also a spiritual act. Both men and women used make-up, such as black kohl, to enhance their eyes and lips. The wealthier they were, the more make-up they wore, so we can see that it was a symbol of status too. These Ancient Egyptians created almond shaped eyes as a tribute to the god Horus. They also wore green paint under their eyes to ward off evil spirits. Cosmetics such as these were so important to the Egyptians that they are often found among grave goods when burial chambers are excavated today.

Native American Indians, similarly used face paint symbolically. Depending where about they were on the continent they had their own short hand and symbols to use in their daily life, or on grander ceremonial occasions and feast days, or in the event of war against neighbouring tribes. It is generally known that red paint signified war, white paint meant peace and yellow paint symbolized death. Green paint for Native American Indians was supposed to improve their ability to see in the dark.

Face Paint and War

Nature did not afford man any natural camouflage and so it has long been necessary for men as hunters to use face paint to camouflage their skin when they are seeking prey. The ancient people used naturally occurring substances with which to disguise their features, such as roots, herbs, clay and coloured stones. In battle, it became an imperative for warriors to be able to hide, unobserved by their enemies, and so camouflage has developed over the ages to what we see today.

For many ancient tribes, the adornment of face paint before hunting or fighting was said to imbibe the wearer with certain characteristics or spiritual power, so certain patterns might suggest someone was strong or fearless or that they were given the abilities on an eagle, or a horse or a buffalo for example. Native American Indians particularly believed that their face paint afforded them new characteristics and greater powers. Frightening make-up could intimidate adversaries and so was particularly popular in battle. Black make-up was used to symbolise death, war, revenge or darkness.

Halfway around the world in New Zealand, the Maori people utilised Ta Moko markings for the same sort of reasons. These were marks that were carved into the skin to form exquisite and delicate patterns. The number and quality of the markings helped to define social class and status. Maoris gained rank from being brave or skilled warriors.

Face Paint for Decoration

During the eighteenth century the fashion for personal adornment was highly favoured. Men and women decorated themselves with red and white paint and powder, which was quite often lead based. This powder caused eyes to swell, attacked enamel on the teeth, altered the texture of the skin, which often blackened, and also caused baldness. At its worst, this face paint could kill you. Both men and women wore elaborate wigs, and shaved off their eyebrows, preferring instead to decorate their eyes with mouse skin instead. They would then cut taffeta patches out and glue them to their faces. These patches symbolized political allegiances and sexual persuasion, but they were also used to cover suppurating sores, open wounds and small pox scars.

From the late 1780s, and the French Revolution, it became less fashionable for women to wear all these accoutrements, because increasingly political and social commentators labelled the women ‘painted ladies’ akin to ‘devil’s spawn’. From 1811 it became more fashionable for men to drop the make-up and wigs in favour of the adoption of a more rugged and manly look. Queen Victoria was strongly against make-up and after husband Albert died in 1861, no respectable woman would be seen wearing make-up in public, and that attitude largely continued through the early twentieth century across the Western world.

Face Paint in Entertainment

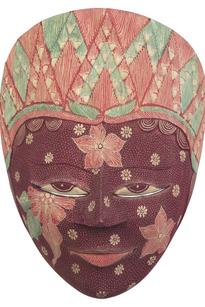

From early times face paint became an essential part of many forms of entertainment and was used to create or enhance costume. Good examples of this include its use in Greek theatre, Chinese opera, within temple dancing in India, and among Geishas in Japan.

Kathakali is an Indian form of theatre that describes stories about ancient Hindu gods and mythological creatures. The make up for Kathakali is elaborate and time consuming. The performer has to lie on his back while a specially trained make-up artist recreates the design for the specific character. The designs are traditional and are instantly recognisable to the audience.

Clowns in circuses have picked up the gauntlet for face paint. Every professional clown in the UK is required to register his or her look with a clown registry! In fact clowns go back to Ancient Greece and beyond, and certainly in Europe, face painting is nothing new. What is relatively new is that children can now have their faces painted at fairs, circuses, fetes and festivals, at children’s parties and by the beach too, and they absolutely love it!

Face Paint and Toxicity

Currently 1 in 8 of the known 82,000 ingredients that are used in cosmetics and personal care items contain chemicals such as carcinogens, Parabens, pesticides, hormone disruptors and degreasers. Some 60% of what we put onto our skin is absorbed into the body, and in spite of popular belief, many cosmetics, including lipsticks, still contain lead. The worst culprits are those that have blue, purple and green dyes. When using face paint it is important to ensure that it is special water based cosmetic paint and is not craft paint or watercolours because these can cause severe reactions. Most modern face paints can be easily washed off, so in the event that any allergic reaction, tinging or heat is felt, the paint should be removed instantly.

Face Paint in Sport

There is a clear link between the face paint used by tribes many centuries ago and the use of make-up and face paint today. It can still be used to show allegiance to a tribe as in certain indigenous populations, or in allegiance to rock groups, such as Kiss, or sports teams. It is becoming increasingly popular for spectators to wear painted emblems for favourite sports teams, or to emblazon the national flag across their face or chest. Professional wrestlers incorporate make up into their overall look too, and can be distinguished by the design they exhibit and even footballers sport a form of war paint. So it’s no surprise then, that face painting is a staple in the sport of Polearmball and does actually contribute to the score achieved in the game.

Written by Terry Houlding

The History and Lore of Face-painting

by Ed Hingston

Just as decisive to a Polearmball victory as scoring deliveries is the game's role-playing element, and getting into character with a great costume and artful face-paint can often mean the difference between winning and losing.

In this article we look at the history of face-painting, exploring its many divergent uses – from magical seduction to savage intimidation, from individualism to tribal solidarity – with the aim of inspiring your own creations, however fantastical or historically accurate you intend them to be.

The earliest estimates attribute the origin of face-painting to our hominid ancestors living in parts of Africa over 400 000 years ago – based on evidence of red, blue, yellow, pink and brown mineral-based pigments for skin coloration. In order to create this prehistoric face-paint, raw materials such as ochre (any of various natural earths containing ferric oxide, silica, and alumina: used as yellow or red pigments) were likely ground up in a sturdy shell using quartzite stones, and blended with crushed bone, charcoal, and a liquid such as water or urine. Although we cannot know for certain what face-painting meant to our evolutionary forebears, we can safely assume that most of their activities were geared towards survival, and that most pivotal of all to this end was ensuring the solidarity of the family, clan, or tribe.

Making use of face-paint to attune an individual to the common objectives of the group was a practice exemplified by those prolific face-painters, the Native Americans. Although to early European settlers the diverse Tribal Nations may have appeared indistinguishable, subtle variations in painted designs differentiated one from another. The Catawba of the Carolinas, for example, circled one eye with black and the other with white to express their tribal allegiance, while a culturally informed visitor to the South-eastern Woodlands could tell an Imosakica Chickasaw from an Intcukwalipa Chickasaw on the basis of whether they wore paint above or below the cheekbones. Displaying tribal affiliation in this way was generally more important for the men, the chiefs and warriors who interacted with groups beyond their own, although women too expressed their solidarity with men at war by wearing similar designs – in much the same way that sports fans today show support for the team they're rooting for.

Face-paint was also viewed by Native Americans as a way of asserting their symbolic union with the world. A common design, for instance, divided the face into two sections, one light and one dark, to mimic the phases of the moon. Their use of naturally-sourced painting materials, applied onto a base of buffalo, deer, or bear fat, was another way of strengthening their bond to the natural environment.

Face-paint was also used to communicate or reflect important events, and every color had a special significance to the Native Americans. Red face-paint, which was derived from ochre, bloodroot (a perennial wildflower native to forests in eastern North America, having a single lobed leaf, a solitary white flower in early spring, and a fleshy rootstock exuding a poisonous red sap), or a mixture of boiled red corn and crushed red berries, was associated with activity, with festivity and celebration, or with going to war (hence the moniker “Red” Indians). A victorious return from war was typically marked by painting the face black with charcoal, shale or earth, a color also applied to mourn the dead in the fashion of some Australian Aboriginal groups. White, from riverbed clay or ashes, was symbolic of peace, as was blue, which also signified wisdom and was made using a special type of clay found in Wyoming, or else duck excrement. Yellow, from riverbed clay, buckthorn berries, moss or cottonwood buds, as well as buffalo gallstones, was used to denote heroism and death, and there is a tale recounted by Black Elk of being called upon as a youth to apply yellow paint to a warrior's face and body before the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. This coloring was meant to symbolise the fighter's readiness to die. In order to mix green, Native Americans combined their yellow and blue pigments, or else they used plant leaves and copper ore, and this color was associated with harmony and healing.

Using face-paint to express moods or temperaments also occurs among the Efik people of southern Nigeria, and a similar system of color-coding exists in Kabuki, or classical Japanese theatre. In the latter case, actors' faces are covered with a white base of rice powder, onto which are drawn expressive colored lines: red to indicate passion, brown to indicate greed, indigo or black for sadness, light blue or turquoise for calm, purple for nobility, pink for youth or cheerfulness, and green for the supernatural.

Face-paint was continually altered by Native Americans to commend certain acts of bravery in battle. For example, as shooting enemies from a distance was viewed as a dishonorable way to kill a man, a warrior who managed to physically touch an enemy and escape unharmed was honored with the addition of a painted hand-print to his face. Likewise, the first man to make a kill in battle was marked by having their face painted black, and among the Ponca a red-tinted face with black stripes was indicative of having collected an enemy's scalp.

In addition to displaying battlefield achievements, face-paint was also used to denote rank within a tribe, the marshal of a war party having two black stripes on his right cheek and the marshal of a camp having only one, while the marshal of council meetings and powwows wore a red stripe across the bridge of his nose.

Similar practices existed in other cultures, such as among the Mbayá, a warlike and powerful people who posed great resistance to the Spanish during their invasion of South America. They were known for their geometric patterns and curling arabesques denoting their position in the social hierarchy, from commoner to noble.

Generally speaking, within the boundaries of recognizable tribal affiliation, cultural symbolism, and the indication of rank or status, Native Americans were at liberty to paint their faces however they wished. In fact, individuals were encouraged to paint their faces in such a way that would honor their own personal spirit guides as well as invite their protection. Pawnee scouts painted their faces white in honor of their guardian spirit, the wolf, and symbols such as the zigzag lightning bolt could be applied to enhance power and speed by appeasing the gods of war, while green was supposed to augment night vision.

All paint was traditionally concocted by shamans (a person who acts as intermediary between the natural and supernatural worlds, using magic to cure illness, foretell the future, control spiritual forces, etc.) who would utter prayers and incantations over it during preparation to imbue it with these valued magical properties. Such was the trust in the powers of the paint that the Chichimec of Central Mexico often went into battle wearing little else.

Face-paint was also considered a source of magical protection in Ancient Egypt, where Kohl, a black substance made using lead sulfide and soot mixed with animal fats, was applied around the eyes to deflect the curse of the Evil Eye.

Pigments were also applied to the eyes for beautification, and green eye make-up from malachite mined at Sinai, the domain of Hathor, goddess of love and beauty, was believed to act as an aphrodisiac. This seductive edge was perhaps Cleopatra's most valuable political asset in her dealings with Rome, having snared both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony before her eventual demise.

So threatening to the reason and wills of men were cosmetics deemed by legislators in eighteenth century England – where the rich used lead-based products and the poor relied on borax and berries – that a law was passed in parliament to make cosmetics illegal, along with other forms of “witchcraft”. Two centuries later, bright red lipstick became a symbol of female independence for the Suffragettes.

If seducing an enemy into submission is one tactical option, then repelling them with fear is another – and intimidation in Polearmball, where opponents may be evenly matched, is a crucial opportunity to score extra points.

The Native American Makah used black paint mixed with glittering flecks of mica to unnerve their enemies, and in Ethiopia, Surma stick fighters paint their faces to intimidate their rivals. The Kainantu of the Papua New Guinean highlands cover their faces in white clay and animal bones, hoping to frighten their enemies by taking on the appearance of the spirits they dread themselves.

In Ancient Britain, Julius Caesar's invading troops were chilled by the resistance of the so-called picti, or painted people, in Scotland. If modern interpretations of the Roman reports are accurate, these Celts probably colored themselves with a blue dye made from the woad plant, or else a copper- or iron-based pigment, to give them the appearance of having greenish-blue skin.

There is further evidence that the ancient inhabitants of the British Isles, and particularly those in Ireland, dyed themselves red using bog iron. These were the Fer Dearg, or “red men” of Irish myth, and were said to cover their faces with the blood of their slain enemies as well.

True or not, such tales from returning soldiers about these blue demons and red savages to the north no doubt bolstered the unnerving reputation of the British Isles, which, with its dark forests, heavy mists, and enigmatic inhabitants, was already fixed in the Roman imagination as a place of the bewilderingly unknown, a place of foreboding, mystery and otherworldly danger. Indeed, it wasn't until much later that the Romans comfortably settled there (with the help of a great wall to keep out the Scots).

In Polearmball, points are given for an impressive appearance and successful intimidation, and face-painting has long served both of these purposes for warriors around the world. Underpinning all of these historical uses, however – whether for solidarity, communication, magic, or war – is the uncanny ability of face-paint to create a separate reality: a space in which individuals can be bound or repelled with extraordinary power, and in which the everyday persona can be entirely dissolved into something greater. Today we see performers, cosplayers, and black metal bands painting their faces for the same reasons.

Having now read the rich lore of face-painting down the ages and around the world, the brush now falls to you. Time to get creative and continue this great tradition by inventing a face-painting lore of your own!

And now a word from the author of this article...

My name is Ed Hingston and I am a freelance writer from the south-west of England. As well as writing video games reviews for AceGamez, I have also worked in publishing, written about culture, society, and history, and continue to blog about things that inspire and annoy me.

My linkedin profile is uk.linkedin.com/in/edhingston

Jeannie A is a slightly eccentric typical tea drinking and biscuit munching Brit, who listens to a lot of rock music. She has a PhD in modern and contemporary British social and cultural history and is an ex-University lecturer. Jeannie is a writer in the broad sense of the word; researching and writing website copy, blogs and articles for a wide range of websites and magazines. Her favourite authors include Stephen King, Mark Billingham, Wilkie Collins, Tana French and Susan Fletcher. Under her pseudonym Jeannie has written a number of horror and short erotic stories. She is currently working on her first novel, which seems to involve a large number of trees. In her spare time Jeannie is a soup maker extraordinaire who likes to listen to the voices in her head, engage in tribal dancing and belly dancing and spend time with her husband and dogs. Jeannie can be found on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Writers-Barn/390815607656543 and on her website at http://www.thewritersbarn.org.