The gong: a glorious history

by Andrew Knighton

Andrew Knighton is a freelance writer and fiction author from northern England. His areas of specialist knowledge include education and medieval history, but he’ll write just about anything rather than go back to a boring office job. When not setting fingers to keyboard he spends his time engrossed in fantasy and science fiction and playing all manner of games. You can find out more about his fiction and views on all things fantastic at andrewknighton.wordpress.com, and hire him from freelance work via elance - www.elance.com/s/aknighton/

Andrew's Links

Gongs have been traced back to around 2000 BC, though historians believe that they existed long before that. As is common with any piece of early progress, it is not until the era when they became popular that we can find gongs in the historical record or the remains dug up by archaeologists. Gongs were certainly used by the Romans at the time of their empire, with a gong found in an excavation in Wiltshire, England dating to around 100 AD, early in the Roman occupation of England. They may also have been in use in the Middle East at that time, and some translations of the Bible refer to gong sounds.

A chau gong, one of the most familiar types, has been found in a tomb dating to early in China’s Western Han Dynasty (207BC to 25AD), showing that they existed in China at the same time they were being used in Rome.

The gong’s presence in a tomb indicates that it already held some special prominence at that time. Though gongs only became popular in east Asia much later, around the 6th century AD, they had probably been used in the region throughout the intervening centuries. The later suggestion that they may have been exported to China from the west, explaining their emerging popularity in the 6th century, is essentially discredited by the Han Dynasty gong.

Chinese tradition says that the gong originated in the country of Hsi Yu, between what is now Myanmar and Tibet. Records from the era of Emperor Hsuan Wu (500-517AD) refer to gongs in Hsi Yu, showing that they were in use by then, and that the region and the instrument were already associated with each other.

By the 9th century, gongs had spread to Java and other islands of the Malay archipelago. The name ‘gong’ in fact comes from Java, which became one of four major centres of Asian gong production, along with Myanmar, China and Annam. Medieval Javanese gong manufacturers produced at least seven different types of gong, and the word referred not to all these instruments but to a specific type – a bossed bronze gong.

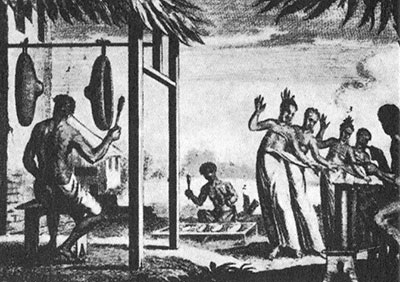

The best gongs were produced at specialist foundries at the city of Semarang on the north coast of Java. The processes of the elite gong maker’s craft were a closely guarded secret, handed down from generation to generation in the privileged families who produced the instruments. As they smelted and hammered the bronze disks into shape, they did so using techniques that combined long tradition with the finest craftsmanship. By the light of a blazing forge, gong makers followed the paths of their ancestors.

With their glorious bass note and beautiful craftsmanship, mystical traditions grew up around gongs in the east. Being touched by one was thought to bring happiness and strength. That association with strength and power continues into their use in modern ceremonies and sports, evoking a link to the strong and successful down the ages. But gongs also became associated with sadder traditions. On the death of a male family member the gong would be struck repeatedly, in groups of three beats. The spirit headed into the afterlife accompanied by the sound of fortune, music seeing him on his way.

Gongs also found more mundane uses. They were used as alarms, much like the ringing of bells in European towns. And like drums they were sometimes used to pass information across great distances, using well known rhythms as a form of language. The sound of a gong echoing across the hills could be used to pass messages from one town to another far faster than a man on horseback ever could.

Despite their use in the Roman world, gongs were slow to gain in popularity as Europe emerged from the Middle Ages. Their first recorded use in western orchestral music was by Gossec in his Funeral March for Mirabeau in 1791. By this time America had won its independence, France had overthrown its monarchy, and England was in the throws of the industrial revolution. Among all this dramatic change came the return of the gong, with Steibelt following Gosse by using one in his Romeo und Juliet (1793), followed by Le Sueur with Ossian Ou Les Bardes (1804) and Spontini with La Vestale, Le Diable (1807). As war raged across Europe under Napoleon, gongs too were all the rage.

With the growing wealth that came from the industrial revolution, Europe’s upper classes developed a taste for the exotic, importing gongs from the east as much to use as display pieces in private collections as for their use in music. Elaborate decoration was the order of the day for these gongs, which were treated less as instruments or religious artefacts and more as works of art. Many of the best tam-tam gongs to leave China for Europe came after the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in 1901, when they were taken as loot from temples and palaces. Not for the first time, art travelled from east to west in hands stained with blood.

In east Asia, gongs continued to be symbols of mysticism and good fortune. Those used by Buddhists for sacred purposes were inscribed with the Mandarin symbols Tai Loi, symbolising the arrival of happiness. They were used in temples and palaces, private homes and public places, and as in the west played a part in orchestral music. They were, to many, the distinctive sound of eastern solemnity.

In the twentieth century, the use of gongs in the west continued to evolve. Experiments in orchestral music saw them vibrated using friction or a bow, laid horizontally, and even lowered in a tub of water to flatten the pitch after striking. They had come a long way from Steibelt’s first step into gongs as percussion.

As film and then television created a popular visual culture, the gong became a icon, once again representing the exotic east, in the way that head dresses symbolised the Plains Indians or the baguette French culture. It was such a powerful and dramatic symbol that the Rank Organisation, the largest film company in Britain, used a man striking a gong as their logo. Generations of cinema goers became familiar with the ‘gong man’.

As gongs became popular more companies across the world sought to produce them, their imitation of eastern craftsmanship having varying degrees of success. The traditional centres of production lost their grip on the market as other manufacturers emerged both in Asia and beyond. But in the 20th century Java sought to regain its place as the premier manufacturer of gongs with a revival of the industry, this time in the city of Surakarta.

So next time you bang a gong, or hear that glorious, rolling sound, just think of the tradition you are connecting to. One of religion, mystery and tradition going back thousands of years. Of secret family crafts and bloody rebellion. Of musical innovation and experimentation. The whole glorious history of the gong.

As befits such a powerful and mythic instrument, the origins of the gong are shrouded in mystery.

Sound Quality

The gong is one of the richest sounding instruments in existence, capable of producing a wealth of overtones and a long sustain. This richness is a result of the component metals and the processes used in making and shaping the gongs. Gongs of good quality are made of bronze (75% copper, 20% tin, 5% nickel) and undergo five processing stages: pouring, hammering, smoothing, tuning and polishing. The gong is struck right in the center, since it is here that the greatest volume and purest tones are produced. Depending on which kind of mallet is used (and on the dynamics) the gong sounds dark, metallic or majestic. The striking points also matter. Each gong has its own extraordinary radiating sound with a unique diffusion of tones and sound colors. The larger the gong, the more multilayered the sound.

History of Gong

The existence of the gong dates back to the Bronze Age, around 3500 BC. Evidence suggests that the Gongs existed at this time in Mesopotamia. Myth has it that sacred gongs included pieces of meteorites that fell from the heaven.

The earliest written mention of the gong was in China in the 6th century (Northern Wei period, during the reign of Emporer Hsuan Wu). Chinese people used gongs for many ceremonial functions and healing rituals. Only certain families were privileged to be gong makers and the process required great skill.

Gongs migrated from China to Java by the 9th century (the word ‘gong’ is Javanese in origin) and became an integral part of their Gamelan Orchestra, where gongs of different sizes and of specific pitches are played together. In his book ‘Music of Java’, Jaap Kunst says: “Gamelan is comparable to only two things, moonlight and flowing water ... mysterious like moonlight and always changing like flowing water ...”. It is believed by historians that China, Annam, Burma, and Java were the main gong producing centers. It is known that these centers produced at least seven gong forms and corresponding sound-structures.

A Roman gong from the 1st or 2nd century was found during an excavation in Wiltshire, England. After a slow migration from Asia to Africa, finally gongs were introduced to the West in the late 18th century, when a few composers started to include gong in some of their compositions. In the second half of the 20th century, they were being used by rock groups.

Types of Gong

Gongs are mainly of three types: (a) Suspended Gongs: The suspended gong is generally a flat circular disc of metal (typically bronze) that is hung in the air vertically. It is not tuned to a specific pitch, and thus makes a loud, multi-toned ‘crash’ when played. The Chau Gong (7" to 80" in diameter), also called a Bulls-eye Gong or Chinese Tam-tam, is the most recognizable kind of suspended gong mainly originating from the Wuhan Province of China. Another example is the rather thinner Wind Gong or Feng Gong. They are lathed on both sides and played with a large soft mallet giving rise to wind-like crash. (b) Bossed Gongs or Button Gongs or Nipple Gongs: Button gongs have a raised center point. They are tuned to a specific pitch and have an added beat note of 1-5 Hz. They are usually suspended or played horizontally. This type of gong is common in Indonesian Gamelan ensemble (the largest one being Gong Ageng and the next largest one being Gong Suwukan) as well as in Kulintang ensemble of the southern Philippines, and (c) Bowl Gongs or Singing Bowls or Meditation Bowls: These gongs are bowl-shaped and rest on cushions. Tibet is considered to be the home of the gong bowls.

The Lore and History of the Gong

by Tania Dey

What is your first reaction when you hear the word ‘gong’? Doesn’t it bring a sense of deep resonating sound? Well, you got it right! The gong is named after the sound it makes. A ‘Gong’ is a percussion instrument consisting of a metal disc that is struck with a softheaded drumstick or ‘mallet’. Gong is one of the oldest musical instruments in the world.

Gong Manufacturers

Besides many traditional and century-old gong manufacturers from east and south-east Asia, the modern gong manufacturers that have gained quite a bit of reputation, include: (a) Paiste, a Swiss company of Estonian lineage making gongs at their German factory (b) UFIP, an Italian company making a range of gongs at their factory in Pistoia, and (c) Sabian: a North-America company making a small number of gongs and zildjian.

More unusual and innovative types of Sculptural Gongs are being made in the recent years by independent gong smiths, most notably by Steve Hubback, Michael Paiste, and Matt Nolan. These gongs serve the dual purpose of being a musical instrument and a work of visual art.

Gong Usage

There are various occasions and purposes for which a gong is required. In ancient times, gongs were used for religious rituals, feasts, for announcing arrival of royalty, to exorcise evil spirits, to frighten enemies, to bring rain, to assist the dying on their journey to the next world, and as spiritual aid for meditation and altering of consciousness. Gongs have also been used in upper class families as waking up devices or to summon domestic help. Gongs have still remained an essential element to communicate, make announcements, make music, accompany life's events, meditate, and heal.

For example, one of the early uses of the Chau Gong was to clear a path for Emperor or other important political and religious officials during a procession. The number of times the gong was struck indicated the official’s seniority. Some gongs are loud enough to be heard from 50 miles away, and were used to signal peasants in the fields, to call people to gather for battle, to signal upcoming train in railroads crossings, to notify the driver of a streetcar or tram when it is safe to proceed, to mark certain hours of a day, and a myriad other occasions in which a loud noise could prove useful. In ancient times as well as today, the gong is used to start sumo wrestling contests.

The Chau Gong or Tam-tam was first introduced into a western orchestra by François Joseph Gossec in the funeral march composed at the death of Mirabeau in 1791. It was also used in the funeral music played when the remains of Napoleon were brought back to France in 1840. In more modern music, the Tam-tam has been used by composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen in Mikrophonie I and by George Crumb. Bossed gongs still play an important role in Indonesian Gamelan orchestra. Gong has been used as a sound effect and as a musical element in a number of movies, TV shows, and music recordings.

In Taoist and Buddhist culture, playing of the bowls have been practiced for centuries and is used for deep meditation, worship and spiritual development. They are also fantastic for simple, daily relaxation. Gong is a very powerful sound healing tool as it is said to produce the ‘aum’ sound, the original sound of the universe. Gong's vibrations can help activate and tune our body’s vibrations, aligning and balancing our ‘chakra’s and energy grids. By playing the gong it is possible to focus and slow our mind and move into a deeper, slower state of vibration. It is at these brain states, like theta (4-7 Hz) and delta (0-4 Hz), that healing and realignment can occur.

In Asian cultures, the gong is an important part of weddings, funerals, theatrical productions and orchestral concerts, now as well as in the past. In the West, people use them in orchestras, in sound therapy, in martial arts and yoga training environments, in self awareness and anger therapy, and even businesses use them to celebrate the attainment of certain targets. Gongs also make rare and decorative addition to personal or musical collections.

Gongs have taken up different names based on their usage and sounds produced. For instance, Opera Gong in Chinese opera consists of an ascending and a descending gong, played together. The large (descending) one is typically used to introduce pivotal players or emphasize particular points in a drama and the smaller (ascending) gong is used to announce the entry of less important players and to identify points of humor. Planet Gongs are possibly the most refined gongs made. Paiste was the pioneer in introducing these planet gongs in 1980’s. They are tuned gongs and the tuning of each gong is based on the fundamental frequency of a given planet or celestial body. The calculations for the frequency of each planet are based on the work of Hans Cousto, a renowned mathematician, and documented in his book The Cosmic Octave: Origin of Harmony, Planets, Tones, Colors, the Power of Inherent Vibrations. Thus, Paiste's Earth Gong is tuned to C sharp because earth itself has been calculated to have a fundamental frequency of C sharp. Planet gongs are ideal sound healing instruments. Their frequency and harmonic overtones will harmonize and resonate with players and listeners to bring the effect of sound-massage. Symphonic Gongs are the gong of choice for Indian ‘kundalini yoga’ practitioners and many sound therapists.

Tiger Gongs have the ability to roar and growl like a tiger, yet can also be mellow like a kitten. Pasi Gongs are very sensitive to the touch and plays beautifully at soft or loud volumes, hence used in circus, plays, and musical performances.

The Largest Gong

According to the Guinness book of world records, the largest gong measures 5.15 m (16.8 ft) in diameter. It was made by Shanxi Baodi Real Estate Development Co. Ltd and was displayed at the Third China Taiyuan International Cooked Wheaten Food Festival, Shanxi Province, China on 8 September 2005. The gong was made of copper and weighed 568 kg (1252 lb).

On the other hand, the Sun Gong used in the annual Paul Winter’s Winter Solstice Concert held at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York is claimed to be the world’s largest Tam-tam gong (7 ft in diameter).

In Film, TV, and Music

In films, the Hungarian animated movie Macskafogó starts with a round cat face, which a mouse strikes like a gong. The Gongman film logo sequence depicts a man striking a huge gong. The gongs used in the films were props made of plaster or papier-mâché, with the sound of the gong done by James Blades on a Tam-tam. Athletes who played Gongman in the film sequence over the years, included boxer Bombardier Billy Wells and wrestler Ken Richmond. On The Muppets Go to the Movies, the muppets parody the Gongman and the pig, Link Hogthrob proudly assumes the role of a gong-beater. In E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, there is a logo at the beginning of the film that shows a muscular man hitting a gong that immediately breaks as he does so.

Gong Ageng used in Kulintang ensemble.

Photo by Philip Dominguez Mercurio is licensed under

CC-BY-SA-2.5

A Sculpture Gong made by Steve Hubback. Photo by Teethmeister is licensed under CC-BY-SA-3.0

In pop music, Marc Bolan and T. Rex had a hit song on their album ‘Electric Warrior’ called “Get It On (Bang a Gong)”. In the closing seconds of the video to Queen's classic song “Bohemian Rhapsody”, percussionist Roger Taylor mimics the Rank gongman by striking a large tam-tam. An eerie gong sounds in WWE superstar The Undertaker’s entrance music. A gong is also played at the end of the song “Dream On” by Aerosmith.

Piggy character beating a gong in The Muppets Go to the Movies. Photo by GonzosNoze. Source: Muppet Wiki.

Souvenir of 1995 Convention, Donald Duck striking Mickey Mouse Gong. Source: eBay

Personal Experience

I have not experinecd a Gong Bath yet, neither can I remember of seeing a gong in some museum. But during my stay in Brussels, Belgium last year (2012) I came across a guy who was sitting on the mid of a street near the Grand Place and was playing a metallic instrument by hand. The sound was so melodious and mesmerizing, that I had to stop by. I made a short video on him and asked him at the end what that thing is called. He said, it is a gong. To be honest I never heard about it before. Never did I know that I will be asked to contribute an article on gong later! This is just a mere coincidence!

To conclude, gongs have been around for a long time and they are more popular today than ever before. This clearly shows the greatness of this unique instrument. A gong is a skilled work of art that proves its quality across many lifetimes. It is an essential part of various occasions and events. It is an instrument of change and great power. So we need to value it and respect it!

In television, a gong was the titular feature on The Gong Show broadcasted in US, where the gong was used to signal the failure of an act by the show’s panel. The title sequence of the Mickey Mouse Club TV show’s original run ended with Donald Duck striking a gong which sounded strange at certain times. In the Pasadena Jones segment of the Tiny Toons Adventures episode ‘Cinemaniacs’, we see the Hamton Pig swinging at a gong and ringing it. In Terry Pratchett's Discworld series novel Moving Pictures, the gong exists in a temple which is a portal to the ‘Dungeon Dimensions’.

About the author

The author, Dr. Tania Dey, is a research scientist, journal editor, freelance writer and photographer. She is well traveled, analytical minded and simply loves writing about anything that interests her. A glimpse of her writing profile can be found at: http://publicationslist.org/tania_dey which includes scholarly publications in journals and books as well as writing for websites, newspapers and magazines.

She can be reached at: taniadey.asp@hotmail.com

A guy playing gong on the street of Brussels.

Photo by: Tania Dey

Extremely melodious and mesmerizing sound of a gong.

Video by: Tania Dey

At the Sound of the Gong…

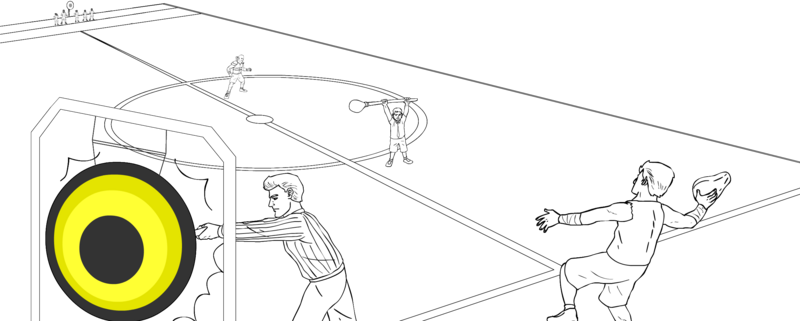

By Mark A. Latham

Players of Polearmball will be familiar with the striking of the gong, signalling the beginning of the action. Waiting for the low intonation of that symbolic instrument heightens the adrenaline of the players, particularly the runners who are about to commence play. And as the sound of the gong reverberates across the field of play, the contest truly begins. It is not by chance that the gong was selected as the starting point for Polearmball, for it is an ancient instrument, with a long history of ceremonial use.

As most people know, a gong is a metal disc that is struck with a mallet to produce a loud, reverberating sound. Technically, it is a type of flattened bell, akin to a cymbal on a traditional drum kit. Gongs are broadly of three types. ‘Suspended gongs’ are more or less flat, circular discs of metal suspended vertically by means of a cord passed through holes near to the top rim. ‘Bossed gongs’ have a raised centre boss, and are often suspended and played horizontally. ‘Bowl gongs’ are, as the name suggests, bowl-shaped, and look more like bells than gongs. Some gongs (primarily the bossed gongs) are tuned to a specific musical note, while others simply offer a ‘crash’ sound (these are often called ‘tam-tams’). In Indonesian gamelan ensembles, some bossed gongs are deliberately made to generate in addition a beat note in the range from about 1 to 5 Hz.

Widely thought to have originated in China, the gong is actually believed to come from the Hsi Yu nation, located between Burma and Tibet. In its long history, the instrument spread across Southeast Asia and beyond. Some proponents of the gong as a mystical instrument place its origin at around 3500 and 2000 BC, and there is certainly evidence for gong-like instruments in use at that time. However, the formalized types of gong that we know today were first recorded around 500 AD.

The first gongs were made of bronze, a metal believed to have been discovered by accident during the agricultural age, as the heat produced by large bread ovens caused tin and copper to run from rocks and combine to create bronze. The gong would have been one of the earliest and simplest forms of metal instrument using this new alloy, and indeed it was originally used to summon peasant farmers from the fields. Some of these summoning gongs are so loud that they can be heard up to 50 miles away! Thanks to their incredible volume, they were also used to clear the streets for police processionals, much like a modern-day police or ambulance siren. When gongs spread to Japan, they were quickly implemented as ceremonial starting devices for sumo wrestling events. This connection to sporting events continues today, and not just in Sumo and Polearmball – the ‘bell’ used to start boxing matches is not a bell at all, but actually a bowl gong.

Eventually, in both China and Japan gongs became adopted for a variety of ceremonial purposes, such as religious ceremonies, weddings, and state processions. In Tibet, they are often used as an aid to meditation by monks. In the Buddhist culture, the gong is used today, as it was in the past, to start the beginning of meditation practice and to call group members together. This spiritual link made the gong popular in ritual healing ceremonies, too, in which it is believed that the resonance of the notes can stimulate the chakras and heal the body of various maladies. Even today, in the west, these ‘gong healing ceremonies’ are conducted by holistic or alternative medicine practitioners.

In ancient China particularly, Gong-making was a spiritual art, veiled in mysticism and even magic. The designs of each type of gong became closely-guarded family secrets, and owning the best type of gong was a sign of status amongst wealthy houses in Asia. All traditional Chinese gongs used for religious purposes are inscribed with the Mandarin characters ‘Tai Loi’, meaning ‘Happiness has Arrived’. They have always been seen as a sign of celebration, and are still often viewed as such today.

One of the most unusual types of gong in the world is the ‘rock gong’, or ‘ringing rocks’. These are large stones, which are struck with smaller stones to create a resonating sound. Rock gongs have been found in various parts of Africa, such as Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Sudan, Uganda and Zambia. The Kupgal petro glyph site in India, discovered in 1892, also includes a large number of rock gongs dating to the Neolithic period. These ancient gongs are not directly related to the metal forms that we know and understand, but stand as an intriguing testament to how people across the world have striven to produce music in similar ways since the earliest times.

The most familiar type of gong to westerners, however, is the ‘chau gong’ or ‘bullseye gong’. The earliest Chau gong is from a tomb discovered at the Guixian site in the Guangxi Zhuang region of China, and dates from the early Western Han Dynasty. The people who lived there were known for their very intense and spiritual drumming in rituals and tribal meetings. As we often think of these large, suspended tam-tams when we picture a gong, it is easy to think of it as little more than a huge cymbal, requiring very little skill to play effectively. However, even in the beginning there were at least seven different shapes of gong, each designed specifically to produce a different sound. As the popularity of gongs spread across the Far East, more designs were created – nowadays traditional gongs are made in China, Thailand, Japan, Italy, Burma, Germany, and many other countries. Great skill was required in playing a gong correctly – the length of the note can be altered, and made to ‘bloom’ earlier by ‘priming’ the gong with an almost inaudible early stroke. This means that playing a gong well is almost an art form, which appealed to the ceremony-minded Japanese in particular. The Chinese players, however, are usually held as the greatest proponents of the gong, and are noted for being able to modify the tone of the instrument by striking it in different places, and with varying force. The musical quality that the Chinese were able to extract from gongs led to it being used in traditional orchestras. Large Asian orchestras sometimes had ‘gong sections’ with up to 18 different gongs!

The use of gongs in entertainment continued to spread. They are often seen in Chinese opera, for example, to announce the coming of players to the stage (they were usually seen in pairs – a large gong for principal players, and a small gong for supporting players). It is these common uses that probably first brought gongs to the attention of western travellers, colonial dignitaries and the like, who carried many artifacts of the Far East back home to Europe. Gongs were seen in symphony orchestras from as early as 1790, and were most notably used in 1817 by Rossini in the final act of ‘Armida’, and later Bellini, Prokofiev and Stravinsky amongst others. Due to its exotic nature, the gong was always seen as a prestigious instrument – they were used with great reverence in the funeral ensemble of Napoleon in 1840, for example, when his remains were returned to France. Within a few decades, the gong became a common feature of the modern symphony orchestra, often used to convey a feeling of climactic drama, fear or surprise. Fine examples of its use are demonstrated in the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, Dmitri Shostakovich and others. Since then, gongs have found their way into modern percussion sections of many orchestras, and have even traversed cultural boundaries into popular rock music. Who can forget the closing note of Bohemian Rhapsody, struck by Queen’s drummer roger Taylor on a large gong? In western rock music, new ‘sculptural gongs’ have proven popular. These specially shaped gongs were pioneered in the 1990s by Welsh percussionist and metal-crafter Steve Hubback (partially inspired by the work of the French Sound Sculptors, Francois and Bernard Baschet), and are used by rock bands and contemporary orchestras across the world. Hubback’s works have been used by many musicians including solo percussionist Dame Evelyn Glennie and rock drummer Carl Palmer.

But of course, in the instrument’s modern translation to the west, not all of its ceremonial origins were forgotten. In nineteenth century Britain, for example, at the height of empire, the gong was one of many Asian items that held a fascination for the Victorians. Upper class Victorian householders used gongs for pomp and ceremony during daily life – the dinner gong to announce the start of a banquet, and even a morning gong to wake household servants.

This practice continued well into the twentieth century in large houses across Britain and Western Europe. Later, the Rank film company famously used footage of ‘the gong man’ striking a huge tam-tam at the start of their motion pictures. This was no random choice of image – the instrument has never lost its sense of mystery and ceremony; it was a symbol that a great event was about to start – a mark of grandeur. Eventually the image of the gong in popular culture led to its wider use. In the 1970s and 80s, for instance, ‘The Gong Show’ was a popular televised talent contest, the precursor, perhaps, to today’s ‘American Idol’ or ‘America’s Got Talent’. In that show, a large gong was struck when a contestant had outstayed their welcome. Similar events ran across the world, from theatrical conjuring shows to tele-visual extravaganzas, where gongs were used as prizes were unveiled or important acts took the stage, leading ultimately to the word ‘gong’ becoming synonymous with ‘award’. At the Oscar awards, for example, actors are often described as ‘winning a gong’ (a term derived from the British Army slang for medal, probably based on the appearance and history of the instrument).

The use of gongs has hardly changed in the Far East, and yet the instrument is now firmly a part of western culture. It is hardly surprising that the world’s largest gong is not in China, but in New York – a 7-foot diameter instrument used at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in an annual Winter Solstice celebration. We see (and hear) gongs on an almost daily basis, but rarely think of the ancient history and spiritual connections of these impressive instruments. In Polearmball, however, the gong is an important feature. As in the ancient sumo contests, the gong heralds the start of an event that is physical, tactical and spiritual – a fitting use for such a prestigious symbol of the ancient world.

Mark Latham is an author, editor and games designer from Staffordshire, UK. Formerly the editor of Games Workshop’s White Dwarf magazine and head of Warhammer 40,000 in the games development team, Mark is a writer of short stories, books and tabletop games, such as Legends of the Old West, and Waterloo. Mark has been ensconced in the worlds of science fiction and fantasy for many years, but his real passion is for history. Mark has a deep obsession with the past, especially the nineteenth century; an affliction that can only be salved by writing on the subject for far longer than can be considered healthy.

Mark's web sites are here: thelostvictorian.blogspot.co.uk

and here: www.facebook.com/thelostvictorian

Musical Instrument – Gong

(in India) by Preeti Poojara

Music and musical instruments have played an important role in Indian culture. They have origins in the Vedic Era era of Hindu culture that produced a Sanskrit style called Veda. In ancient times, knowledge was passed on verbally from generation to generation in forms of vedic richas, sutras and shlokas. Vedas, Shruti and Smriti were sung melodiously by the Rishis and their disciples. Religious rituals and rites were performed with rhythmic and melodious recitations of hymns from Samveda. During the Vedic period from about 1100 BCE to about 150 BCE , chanting and music was an important feature of rituals. It was believed that instrumental music, singing, and dancing were able to propitiate deities. Musical instruments during the Vedic period were of different types consisting mainly of flutes, drums, and Gongs.

You can find references of different musical instruments in several ancient texts such as the Upnishad, Samhita, Ramayana, and Mahabharata. Various performing arts in India are rich with mythological elements. The first reference to Indian music was made in 500 BC by Panini, a great scholar. 2000 years old Sanskrit text Natya Shastra by Bharata presents treatises on dance, music and theatre. Five systems of taxonomy to classify musical instruments are described in Natya Shastra. Various types of musical instruments have been recovered from different archaeological sites in India. Some of them were seven holed flutes, harp like stringed instruments and drums.

Many musical instruments mentioned in ancient texts date back to 5000 years BC. Musical instruments discovered during excavation of pre-historic sites consist of crude drums and some other musical instruments made from bones, bamboo and animal skin. Buddhist sculptures from the 5th century BC to 2nd century AD depict some advanced instruments belonging to the string, wind and percussion categories of musical instruments. .

In ancient India, musical instrument gong was known as Kansya or Kamsa. The name is derived from the Samskrit term kamsya meaning bell metal. The terms thali, tala, kamsyatala and many other names have been used for the musical instrument gong in different regions of India. The names used for flat gong vary from region to region. They are known as thali in Hindi, ghadiyal in Rajasthani, semmankalam in Tamil, jagte or jagante in Kannada and chenkala or chennala in Malayalam.

Kamsa or Knsya “bell metal”

Gangsa flat gongs from Kalinga.

The early presence of the gong in India dates back to 2nd century BC to 7th century CE. A bas-relief of a gong was found in Amaravati, now in the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh. Amaravati is associated with many Buddhist Tantric teachings. It was an important place during composition of the Kalchakra Tantra in Buddhism. Even today, Amaravati is famous for its Buddhist sculptures and inscriptions found during excavations. Amaravati archeological museum displays Buddhist relics dating back to 3rd century BC. It is not clear from the relief and pictures, if the gong found during this era was a flat gong or a bossed gong. The picture depicts two men carrying a gong hung from a bar on their shoulders. One of them is beating the gong with a stick.

Another instance of a gong is found in a 12th century relief from the temples in Hoysala. Hoysala dynasty was one of the prominent empires in South India between the 10th and 14th centuries. During the Hoysala era, art, literature and architecture in South India flourished lavishly. The relief from the Hoysala temple depicts a 30 to 40 cm gong which is flat and even shaped. It is carried by a player in his left hand suspended from a rope inserted through a hole in the rim of the gong. He strikes the gong with a mallet in his right hand. He is accompanied by two other musicians playing a double membrane drum hanging from the neck and shoulders with a strap. They are beating the drums with their two hands. It was a prevalent practice to carry bossed gongs with double headed drums in religious processions during the 10th century.

In North India, the presence of gongs had been noticed during historical times. The gongs found in North India were usually flat gongs made of bronze, either with raised rims or flat rims. They were known as Thali. The method of playing a gong varied from place to place. Either the gong was held in the left hand and beaten by a stick in the right hand or it was placed on ground and beaten with one or two sticks. You can find pictures of flat gong with straight rim or Thali found in Rajasthan carried by a group of women singers. In these pictures, the gong is placed on the ground with one end on the ground and the other end resting on the knees of a sitting woman. She beats the gong with both hands; with her right palm she strikes the center of the gong and she uses four fingers of her left hand to beat the edges of the gong. The rest of the women in the group clap with their hands and sing. Similar techniques were employed in North Luzon using flat gongs known as gangsa.

In South Rajasthan, some illustrations display rimmed gong or thali with its rim widening outwards. The gong is placed on the ground facing down. The player dampens the rims of the gong with his left hand and beats the basic beat in the center with his right hand. Thali is usually accompanied by two drums. Similar ensembles were found in Java and Bali referred to as gamelan. Flat gongs are abundantly found in temple reliefs in India and Java. They are also found in ship wrecks dating back to 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th centuries.

Thali or flat gong is referred to by different terms in Rajasthan and Utter Pradesh. In Pushkar, Rajasthan, it is known as tali, which is a brass plate with a raised rim. A similar gong is known as thal in Maharashtra. In South Karnataka, a hand-held bronze gong is known as tala. In Banaras, a small flat gong with two holes in the rim to insert a rope is called tala. A Priest of the temple holding a gong in his left hand beats the flat surface with a small round wooden stick. Tala is accompanied by an hourglass shaped drum called Damaru.