Women in War, Women in Sport

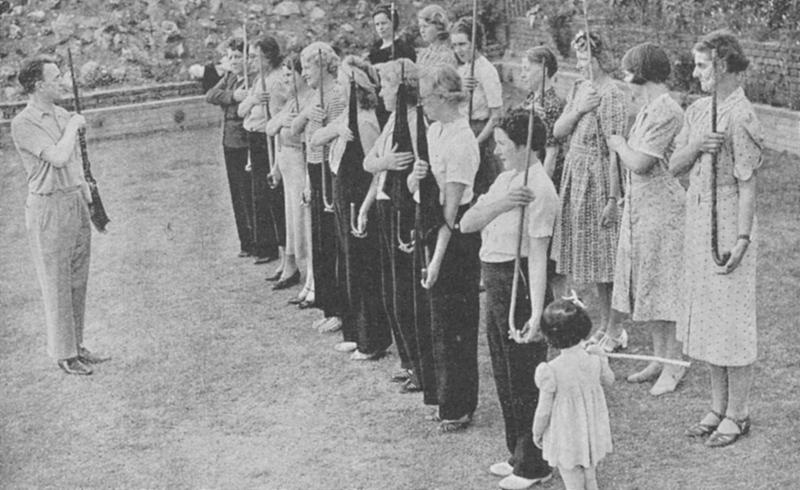

Women in wartime are often portrayed as faithful keepers of the family hearth, rather than warriors themselves. But there are strong female war leaders scattered throughout human history, and women still go into battle every day whether in a soldier’s uniform or sports paraphernalia.

War Heroines in History

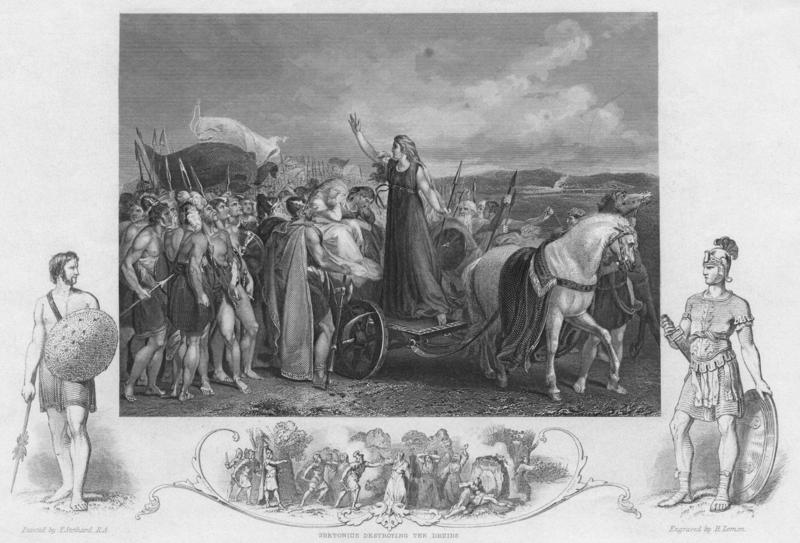

After the Roman conquest of Britain, a woman named Boudica famously fought back against Roman rule. When her husband and king of the Iceni tribe died, the Romans seized control of his lands and people, flogged Boudica, and raped her two daughters to whom the dead king had willed half his kingdom.

Boudica fought back, rallying other tribes to join the battle. By delaying her attack until the Roman governor was on the other side of Britain, she managed to raid and destroy several large Roman-occupied cities, including London. (This type of tactical thinking would have made her a great Polearmball player!) Historians believe that in the end, she met her death either in battle or by suicide to avoid capture.

Another well-known heroine of battle is St. Joan of Arc, who motivated and led the French in the Hundred Years' War before being captured and condemned to death. Even after her capture, she risked several daring escapes including a jump from a 70ft tower. Her habit of dressing in men’s clothing is common among historical female warriors, many of whom pretended to be male in order to fight alongside the men.

Heroines of Modern Battle

The number of women in the military and in law enforcement is rising. The Pentagon’s latest figures show that there are more than 200,000 women in active military service, and in 2013 the Defense Secretary signed a directive to allow women to serve in front-line combat posts.

Some opponents are highly critical of opening active combat roles to women, raising a variety of complaints:

Women are physically weaker than men

Women distract men

Women’s menstrual cycles make their performance unreliable

Women are more likely to be psychologically traumatized by battle

Women are more likely to give up information if captured

But all of these criticisms are based on sweeping generalizations, proving more about the commentator’s sexist mindset than about the viability of women in battle.

How women perform under the physical and psychological strain of battle or competition depends on the woman, not on her sex.

Women in Sport

Look at martial arts for examples of women’s physical abilities. Legend tells us that the popular Chinese martial art Wing Chun was developed by a woman, Yim Wing Chun, who trained under a Buddhist nun named Ng Mui during the Ching Dynasty.

Modern-day women can be martial arts winners, too. In the 2012 Olympics, female martial artists like Diana Lopez and Hou Yuzhuo competed for medals in Judo, Tae Kwon Do and Wrestling. Tiny Brazilian competitor Sarah Menezes won the gold in the 48kg category for Judo, while Kayla Harrison won gold for the United States in the 78kg category, proving that women of all sizes and nationalities can excel in sports that represent battle situations.

Ball games like rugby and football have traditionally been far less accepting of female players. The earliest documented female rugby player was Emily Valentine, who played for her school team in Ireland in the late 19th century and scored a try. A few years later, a New Zealand all-female rugby team formed, but canceled their tour of the country in the face of public disapproval.

In American football, there were no all-female teams until very recently. Women were generally unwelcome on men’s football teams, or limited to low-contact positions like placekicker or placekick holder. In 1997, placekicker Liz Easton became the first woman to score in a college football game. Patricia Palinkas, the first woman to play in a professional football league dominated by men, was a placekick holder for her placekicker husband.

Polearmball is more respectful of women’s athletic abilities and encourages female players to join the game along with male players. As a role-playing battle game, it honors women’s contribution in war and sport around the world and throughout history.

How Women Excel in Polearmball

In the excitement of a Polearmball battle, both men and women must use their strengths to succeed. Thinking tactically, motivating your cohorts and escaping the enemy like Boudica or Joan of Arc are important skills in this game—no less important than applying brute strength or outrunning your opponents.

Polearmball is a mixed-sex sport and a great equalizer. Tall and short athletes each have their own advantages in the game, and physical strength is not the deciding factor in victory. Instead, teamwork and strategy are vital from your very first game, while athleticism in the form of strength, speed, agility or endurance is something a player can develop over time.

In so many battles, women have stood beside men to fight. In so many cultures, women play their part in hunting for food and supplies. In so many ways, women have all the necessary skills to become great athletes and team leaders. Polearmball reflects this, and is open to all.

BIO: Meet the author of this article...

Sophie Lizard

is a freelance writer fascinated by culture and technology. Visit http://BeAFreelanceBlogger.com to build your own freelance writing career online, or find out more about Sophie's work at http://LizardCreativeChaos.com

The Warrior Within: Women in War, Women in Sport

Introduction Written by Jeannie

Women’s exclusion from public life is a social construct conveniently created to allow men to control property and paternity. In pre-history humans lived in groups in which men and women were fairly equal, both were active in providing food for the wider community, and child care would have been shared among older members of the tribe. There is no reason to assume that women were incapable of using weapons or waging war when required. Females only lost status much later, as the wandering tribes settled into an agricultural way of life. Not all women were happy to remain sedentary however, and this essay seeks to demonstrate that women have pushed at the boundaries and the ties that constrain them ever since. Every woman has a warrior buried deep within, and increasingly they are participating in war and sport and showing the world that they are every bit as intimidating as men.

Women in prehistory

The conventional idea that society has, that women were passive gatherers in pre-history, does not have any basis in fact. This notion actually stems from nineteenth and twentieth century constructs derived from the way scientists, historians and archaeologists (mainly men) felt that women should behave. Did prehistoric woman sit by the fire and knit, waiting for her brave man to come home? No of course she didn’t. Projecting the ‘ideal’ 1950s style nuclear family (itself a non-starter) back several millennia is a mistake. Macho males and reticent women are part of a fabricated scenario in which warfare and male dominance are linked to the idea that human males have always been innately aggressive and women have not. This is nonsense.

Evidence about our fore-mothers shows they were much more aggressive than has often been assumed. They were active: they hunted, they cared for their families, they provided for their young and they selected their male partners. Research shows that early man and womankind were nomadic, wandering from place to place, much as the aboriginal peoples of the US, Africa and Austral-Asia have done until more recently.

Public men vs. private women

From traditional scholarship we have the assumption that women stayed mainly in the private sphere while man inhabited a very public world and in many ways this is true. The family, primogeniture and inheritance have always been a primary concern for mankind. Men have constructed societies, particularly in the West where women have been controlled socially, culturally, politically, economically and at times physically, simply so that men know that their offspring are their own. This ensures that lands, deeds, titles and property can be handed down from father to son. Marriage is a social construct for example, and an institution that generally allows one partner per person. In cases where marriage laws and customs allow more than one spouse, this is so that men can have more than one partner, not women.

However it is too simplistic to state that women have never really operated in the public sphere. Certainly the private sphere became more regulated with the development of the middle classes in the nineteenth century. Prior to this, some aristocratic women had a measure of freedom, particularly in politics and intellectual and cultural circles. However, lower class women, the merchant classes and less well to do women have continuously operated within the public sphere throughout history. Contributing to the family economy was a woman’s job just as much as it was a man’s job. Men, women and children worked hard to earn the pennies that would keep bread and cheese on the table.

Of course there are innate differences between the genders that operate to advantage one sex over another. Women have pregnancies of course, and until recently there were high maternal mortality rates in childbirth. Women breast feed and are carers. For centuries fashion decreed that women wear corsets, bustles, hoops, stays and long gowns that hindered movement and even breathing. Male discourse in early scientific thinking, particularly during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, constructed female maladies relating to menstruation and menopause that severely restricted –in men’s eyes – the capacity of women to be rational, independent, intellectual thinkers. They could not be trusted to run their own affairs, or run an errand, let alone a political race.

During the nineteenth century we therefore see women laced so tightly into their corsets that they could barely move, walk or sit. Their skirts were sometimes so wide they could not pass through doors. Inability to breathe properly caused the constriction of diaphragm and lungs, meaning that women needed to rest frequently and avoid physical exertion, and of course many of them fainted often, meaning that they became a weak and feeble stereotype that played straight into the hands of their male detractors.

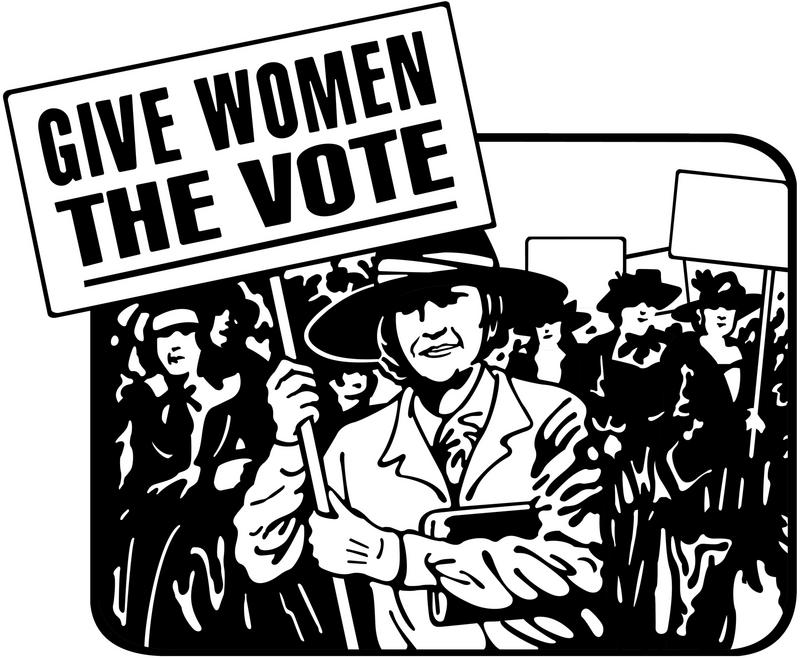

Given all these restrictions it is little wonder that middle and upper class women were forced to retire from public view temporarily until the First World War and a lack of available male labour pushed women to the forefront of the public sphere once more. Suffragists and suffragettes had been gamely fighting for women’s rights from the end of the nineteenth century in countries as far afield as New Zealand, the UK and the US; but it was actually the need for women to step into men’s work boots and enter the labour force during the First World War that forced the issue, particularly in Europe. War made a big difference but of course very few women were to see active service because war is defined as the realm of the public man; just as sport is.

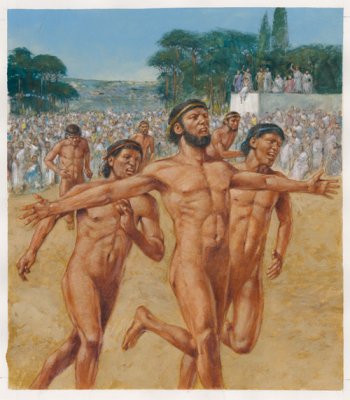

Sport and War

The skills needed on the sports field are akin to those required on the battle field. According to Professor J. A. Mangan - British social historian and academic - military activity becomes community recreation and vice versa. Both sports and war are a legitimate outlet for ‘patriotic aggression’ and both represent the best and worse that a nation can possibly offer. Mangan notes that both sport and war heroes are valued as symbols of national prowess, quality and virtue. The sacrifices of war, working for the greater good, keeping the home fires burning and the ‘Dunkirk spirit’ pulls communities closer together. Similarly, regional and national sports bring people closer, and help to creative a collective national memory to be celebrated or commemorated forever after. Both sport and war shape our national identity.

Elite schools in both Europe and the USA have long linked sports to militarism endorsing the idea by General Wellington that battles were won and lost on the playing fields of youth and that athletics instilled character among the young. It is reasoned that the better the sports program the better the soldier.

Mangan asks: what is sport except a competition without killing? Both war and sport involve the victory of one side and the abject humiliation of their opponent. They both share numerous characteristics. Sport teaches us how to become battle ready; we learn loyalty to others, obedience; discipline; teamwork and cooperation. We learn how to follow and how to lead. It coaches us in aggression and endurance.

The traits that Mangan and other sport and social historians discuss are fiercely masculine. Mangan describes how women turn inwards to face the private sphere while men face outwards, embracing all that is public and heroically confronting its problems, and while this is largely true, we cannot accept this view of the world as natural and all encompassing.

Women’s Engagement in Sport

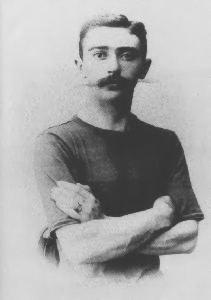

The Modern Olympic Movement was founded by Baron de Coubertin in 1896 when he pompously declared that an "Olympics with women would be incorrect, unpractical, uninteresting and unesthetic [sic]," before overseeing the first modern (and men only) Games.

He was carrying on a long tradition where women had been largely exempt from sport and competition. Many male physicians feared that women were far too weak and vulnerable to exercise safely. A woman’s place was as a spectator, in the stands or on the banks, applauding her menfolk.

The first Olympics had been held in Greece in 776 BC and women were excluded straight away.

Their solution to this? They held the Games of Hera every four years, and honoured the Goddess of women. By 396 BC the Spartan Princess Kyniska had won an Olympic chariot race, but because of her sex she was barred from collecting her prize. From this point on the history books are largely devoid of discussion on women in sport. We do know that - depending on her place in societal hierarchy and her culture – women could ride and hunt, farm and learn how to use weapons. However, on the whole, women in sport were neither encouraged nor praised. History makes women mute.

Between 396 BC and 1900, the vast majority of women who are mentioned in relation to sport are aristocratic, noble or upper class. In 1406, Dame Juliana Berners for example, wrote a book on sports fishing. In 1522 Mary Queen of Scots is noted as a golfer. From the eighteenth century there are dribbles of information about women balloonists, ice skating (Leeuwarden, 1805), horse racing (1805) and other aristocratic pursuits.

In 1850, Amelia Jenks Bloomer caused a scandal by publicizing loose fitting pants worn under a skirt. These ‘bloomers’ actually allowed women a measure of physical freedom they otherwise could not have managed.

In 1522 Mary Queen of Scots is noted as a golfer.

Amelia Jenks Bloomer

Unfortunately it would take another century before Hollywood latched onto the style and made it generally acceptable for women throughout the West to wear pants and trousers.

Through the 1860s and 70s women competed in the refined pursuits of croquet, tennis, baseball, hockey and swimming, but it was 1888 before the next major breakthrough came. A bicycle was invented that had two wheels of equal size (as opposed to the penny farthing with its enormous front wheel) that was powered by a chain drive. The bicycle was a huge hit among women especially in the US. Certainly at this time, women were becoming more adventurous; there were reports of women mountain climbing, parachuting (from a balloon in 1891) and shooting.

Unfortunately, by the 1900s there was a backlash against these active and trailblazing women who were seen to be more and more of a challenge to the male status quo with their absurd demands for the vote, higher education and equal rights. Physical instructors at this time were totally opposed to the idea of women in competition on the grounds that it was an unfeminine and therefore undesirable trait for women to possess. But it was too late; the flood gates were breached and women were swarming through. In 1900, 19 women took part in the Olympic Games in Paris, in the sports of tennis, golf and croquet. By 2012, 4847 women competed in the London Olympics and in fact for the first time ever, every nation that did compete had at least one woman on their team which was a special achievement indeed!

Women Warriors

Throughout history we perceive that war and fighting have been the province of men only, but actually that is not, and has never been, the case. Obviously women would defend their homes and families to the last breath if they needed to; and if their men folk were away on a campaign it stands to reason that women would have been part of a town’s militia. A medieval lady would have taken charge of the defence of the family lands in her husband's absence certainly but we also know that aristocratic women led armies in the field, both in local conflicts and in expeditions such as the Crusades.

Many women have disguised themselves as men in order to see action at the battlefront but that is not the case for all. The Rig-Veda, an ancient poem of India (written between 3500 and 1800 BC) tells the story of a warrior Queen, Vishpla, who lost her leg in battle, was fitted with an iron prosthesis, and returned to battle. We also know that the ancient Greeks had legends of a group of women warriors called the Amazons, possibly based on stories about Scythian women of the 4th and 5th Centuries BC. Archaeological finds of Scythians have included female skeletons with bows, swords, and horses. A similar excavation by the Museum of London found the remains of a woman who is believed to have been a gladiator in a Roman cemetery in London. The British Museum has a second-century relief carving of two women fighting. Each has a short sword and a shield. Ancient women were fierce, there’s no doubt about that!

Although Roman law was generally very much against the idea of women as rulers, the Romans in Britain took a more practical line and recognised established British Matriarchies. Boudicca for example was the widow of King Prasutagus of the Iceni, and regent for her two daughters who inherited half of the kingdom. The other half was given to Rome. When the Romans complained about being given only half of the kingdom in 61AD they provoked a revolt. According to Tacitus, Suetonius, the general who finally defeated Boudicca, in the ranks of the Britons, “there are more women than fighting men." Boudicca was eventually defeated and awarded an expensive burial by the Britons who had come to value her bravery.

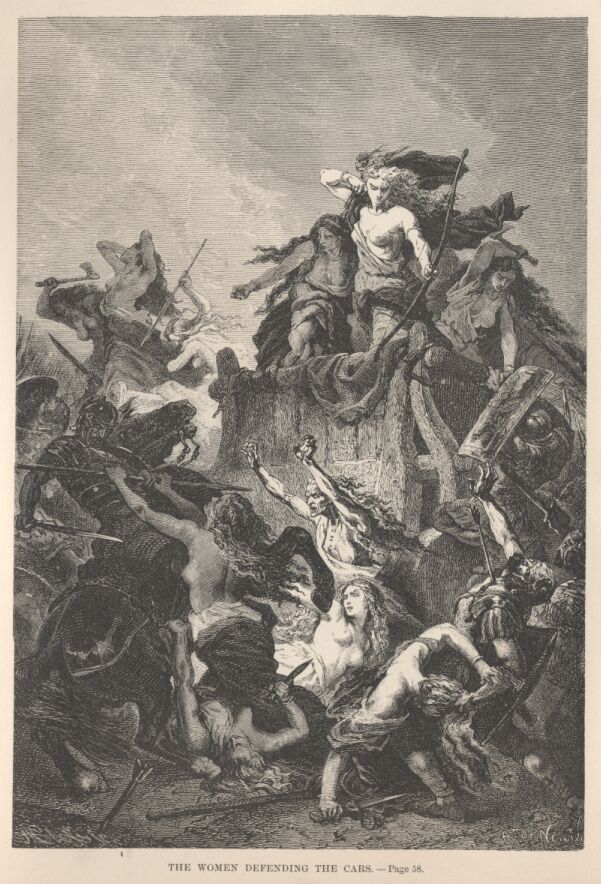

The Celts at this time were known for being particularly fearsome. They are reported as standing ‘as tall and broad as their menfolk’, and the Roman historian Plutarch described a battle in 102 B.C. between Romans and Celts thus: "the fight had been no less fierce with the women than with the men themselves... the women charged with swords and axes and fell upon their opponents uttering a hideous outcry." Similarly, Roman author, Ammianus Marcellinus, described Gaul women as being even stronger than their husbands and fighting with their fists and kicks at the same time "like missiles from a catapult".

Women dressed as men in the Civil War

Boudicca

Viking archaeology has uncovered remains that point to women’s active role in their affrays. DNA studies of corpses in an Anglo-Saxon in North Yorkshire, UK (AD450-650) found that two bodies buried with spear and knife were women, and the body of an Anglo Saxon woman (circa 500AD) with a dagger and shield was found just outside Lincoln, UK. It is also known that Aethelflaed, eldest daughter of Alfred the Great of England and known as the Lady of Mercia, led troops against the Vikings during her father's reign and was responsible for building many fortifications.

Women were also involved in crusades. It is interesting that the pope in 1189 felt the need to issue a Papal Bull to prohibit women from joining the Third Crusade. Women ignored the Papal Bull anyway of course. The queens - Eleanor of Aquitaine, Eleanor of Castile, Marguerite de Provence, Florine of Denmark and Berengaria of Navarre - are known to have gone on Crusade, and Guilbert de Nogent who wrote a history of the Crusades mentioned "a troop of Amazons" accompanying the Emperor Conrad in Syria, along with women Crusaders in the army of William, Count of Poitiers.

Slightly later, during the sixteenth century we have much evidence of women warriors. The Irish Princess, Graine Ni Mhaille (1550-1600) was a pirate who commanded a large fleet of ships. She attacked the English navy, shipping and coastal towns, and yet Queen Elizabeth accepted her claims to land. Meanwhile in 1568, two sisters, Amaron and Kenau Hasselaar, led a battalion of 300 women who fought on the walls and outside the gates to defend the Dutch city of Haarlem against a Spanish invasion. During the English Civil War Queen Henrietta Maria was actively involved in King Charles' campaigns and marched at the head of one of his armies, but King Charles issued a proclamation banning women who were with the armies during the English Civil War from wearing men's clothing, suggesting this was quite commonplace and undesirable.

During the Norse era in South Iceland this woman was buried in this position along with a knife

1000 AD

There are plenty of instances thereafter of women disguising themselves as men in order to fight. Deborah Sampson Gannett (or Samson) disguised herself as a man and fought in the American Revolution and in 1771 Naval Seaman Charles Waddall was found to be a woman when she was being stripped for a flogging. In 1781 Naval seaman Margaret Thompson, using the name George Thompson, also revealed that she was female after she had been sentenced to be flogged. Eliza Allen fought in the Mexican War of 1846-1848 disguised as a man. It is estimated that 750 women disguised themselves as men and fought in the American Civil War so great was their need to fight for a cause.

Other women became warriors to exact revenge. In 1775 Jemima Warner took her deceased husband's place in the ranks during an American army expedition into Canada led by Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery and Colonel Benedict Arnold. In 1777 Mademoiselle Leverrier fought a duel with a naval officer, Duprez, who had jilted her, and again in France in 1828, a young girl fought a duel with a man who had abandoned her. Perhaps most famously, Catherine the Great led rebels in a successful coup against her husband Tsar Peter of Russia. She wore a soldier's uniform and directed the strategies of her numerous wars herself, right up until 1796.

Baron de Coubertin

During the Middle Ages aristocratic women were encouraged to engage with hunting with both hound or hawk and of course they were well versed in equestrian arts, so it is likely that they participated in some fashion in the tournaments of the time and would have been battle ready.

The Irish Princess, Graine Ni Mhaille (1550-1600) was a pirate who commanded a large fleet of ships.

in France in 1828, a young girl fought a duel with a man who had abandoned her.

During the First World War (1914-1918) there are numerous examples of women on active service. Helene Dutreux was the first of a number of women that the French government officially allowed to become military pilots during the war, and more than 200 women fought in the Polish legion in 1916, including Sophie Jowanowitsch and Stanislawa Ordynska. Marie Marvingt served as an infantryman in the French Army in 1915 and then as a military pilot flying bomber missions, and Flora Sanders, an Englishwoman in her forties fought in the trenches with the Serbian army. The Turkish army at Gallipolli had women snipers and the majority of Russian Cossack regiments included a few women.

The fashion continued throughout World War Two also, with 70% of the 800,000 Russian women who served in the Soviet army fighting at the front. One hundred thousand of them were decorated for defending their country.

Helene Dutreux

800,000 Russian women in World War Two served in the Soviet army fighting at the front. One hundred thousand of them were decorated for defending their country.

Modern Day Women Warriors

Emancipation for many women (but not all) has continued apace during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, particularly in the West; although some changes are slow to be brought around. Loretta P. Walsh (April 22, 1896 – August 6, 1925) became the first American active-duty Navy woman, and the first woman allowed to serve as a woman, in any of the United States armed forces other than as a nurse, when she enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve on March 17, 1917.

In the UK, the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) was created in 1917, three years into the First World War. After a number of terrible losses and bitter fighting, the navy was short of sailors and so the Admiralty recruited 3,000 women to ‘Free a man for sea service’. The women were restricted to domestic tasks at first, replacing male cooks for example but by the end of the First World War, the role of the Wrens had expanded to a limited extent with the women also working as telegraphers, electricians and code breakers.

In the US, more than 150,000 American women served in the WAAC during World War II and by the end of the war more than 350,000 women had served in the U.S. military carrying out essential noncombat responsibilities. The idea that women could be anything but nurses was very difficult for people to accept. There are currently 200,000 active-duty women now in uniform in all the services across the USA. The US military officially lifted a ban on female soldiers serving in combat roles in January 2013. They have stated that anyone qualified should get a chance to fight on the front lines of war regardless of their sex. Pentagon Defence Secretary Leon Panetta said "Everyone is entitled to a chance.” At the moment women make up about 14% of the military's 1.4 million active members and more than 280,000 of them have done tours of duty in Iraq, Afghanistan or overseas bases where they helped support the US war effort in those countries. With this honour comes sacrifice as 152 women have been killed in the conflicts.

The US military officially lifted a ban on female soldiers serving in combat roles in January 2013.

Women in polearmball

Polearmball is an innovative game that pitches teams against each other. The beauty of Polearmball is that teams are comprised of mixed gender and so women are competing on their own terms with their male colleagues. The pre-historic warrior within can finally be unleashed after several millennia remaining largely dormant while women languished and wasted away while hidden in the depths of the private sphere. Polearmball gives women the chance to release their kiai, to handle a weapon, to dress up, to paint their faces and to take on the world. Polearmball gives every sporting woman the chance to wage war and be fierce!

Conclusion: The warrior within

Every woman has a hidden goddess, but even more essentially than that, within every woman is a fierce warrior. Women were never supposed to sit by the fire and be passive creatures. They were supposed to join their mates on the hunt and to kill and collect the food that helped the tribe to survive. When medieval women found their castles or houses attacked by marauding gangs of vigilantes, did they run? No, they fought back. Small groups of women and individual women have always participated fully in war or sport, and they stood up to the machinations of society and culture and bravely held the banner for the rest of us to follow.

Women’s passivity and seclusion by the hearth, their absence from public life – in politics, in employment, in sport and in war – was constructed by society in order to protect property and paternity. There is no longer any need for this. Women participate at the highest sporting levels and they are sent into war zones. There are no excuses any more. Throw back your heads ladies, and roar! The women are coming!

This article has been brought to you by Jeannie!

Jeannie A is a slightly eccentric typical tea drinking and biscuit munching Brit, who listens to a lot of rock music. She has a PhD in modern and contemporary British social and cultural history and is an ex-University lecturer. Jeannie is a writer in the broad sense of the word; researching and writing website copy, blogs and articles for a wide range of websites and magazines. Her favourite authors include Stephen King, Mark Billingham, Wilkie Collins, Tana French and Susan Fletcher. Under her pseudonym Jeannie has written a number of horror and short erotic stories. She is currently working on her first novel, which seems to involve a large number of trees. In her spare time Jeannie is a soup maker extraordinaire who likes to listen to the voices in her head, engage in tribal dancing and belly dancing and spend time with her husband and dogs. Jeannie can be found on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Writers-Barn/390815607656543

and on her website at http://www.thewritersbarn.org.

Written by Jeannie